By Crimson Jordan

Black History Month has always been about telling the stories that have gone untold—the triumphant stories of the societal impact and progress made by those who were not always accepted as members of society themselves. In school, we often learn of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., George Washington Carver, Malcolm X, and Madame CJ Walker. As the years go on, we hear these same stories over, and over, and over again. And while these stories are important to celebrate and pass on, we are in desperate need of more stories, stories that are more representative of the Black community has a whole—and of Black queer people.

Black queer stories are slowly beginning to be elevated—the narratives of Marsha P. Johnson, Audre Lorde, Gladys Bentley, James Baldwin, and Bayard Rustin, among many other queer Black figures in history, confirm that the intersections of race and queer identity are nothing new. These particular individuals, however, are known because of the accessibility of their existences and the privilege of their historical preservation. They hail from places like Harlem, Chicago, and California—places that often receive national, even international, attention. In the South, however, we haven’t always had the advantage of having our narratives spotlighted. We haven’t always had the ability to freely tell our stories, and there has been so much history lost or temporarily misplaced because we haven’t been able to proudly preserve it. In an attempt to rectify this issue, I am sharing five stories of five Black queer southerners with you. Read this and pass it on.

Dr. Walter Charles Law

Born March 26, 1951

Houston, TX

Dr. Walter Charles Law

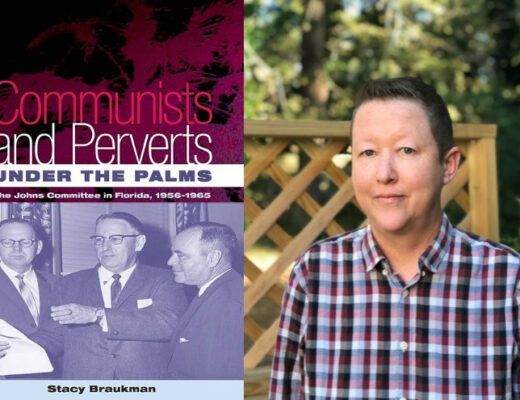

The story of Dr. Walter Charles Law cannot fully be told without recognizing his active role in both Houston’s LGBTQ history and the city’s history as a whole. Known as Charles Law to most, the local activist and gay community leader had a reputation for his remarkable intelligence and inspiring ability to put words into action. He earned his doctorate in education from Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and was employed by Texas Southern University (TSU), a historically Black university where he served as a university archivist, published the first bibliography of university documents, and proposed and pioneered an archival system that TSU still uses to this day to house their official records.

Law was also the chairman and founding force of the Houston Committee, a social and political organization for Black gay men in the 1970s. The organization, under Law’s leadership, held annual conclaves that featured Black LGBTQ representation from all over the country. He was also an integral part of planning the historic 1978 Town Meeting I where, as executive committee co-chair of the meeting, he had a hand in the initial efforts to establish the same sustainable institutions that developed protections and services for Houston’s LGBTQ community—some that continue to serve the community to this day.

Though Law’s impact greatly affected Houston and its surrounding areas, it did not stop there. In 1979, Law delivered a profoundly inspiring speech at the very first National March on Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights. Sharing the stage with other queer heroes like Audre Lorde, Leonard Matlovich, Kate Millet, and Allen Ginsberg, he spoke in front of what is estimated to be between 75,000 and 125,000 LGBTQ people and allies from all over the country, marching together to demand equal rights and to urge protection under the law for a community that was being oppressed and dehumanized on a national level. Law’s speech called for the community to unify, to take initiative, and to have unyielding hope, in order to achieve the kind of future for which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Harvey Milk fought and died. You can listen to his speech here.

Bessie Smith

April 15, 1894–September 26, 1937

Chattanooga, Tennessee

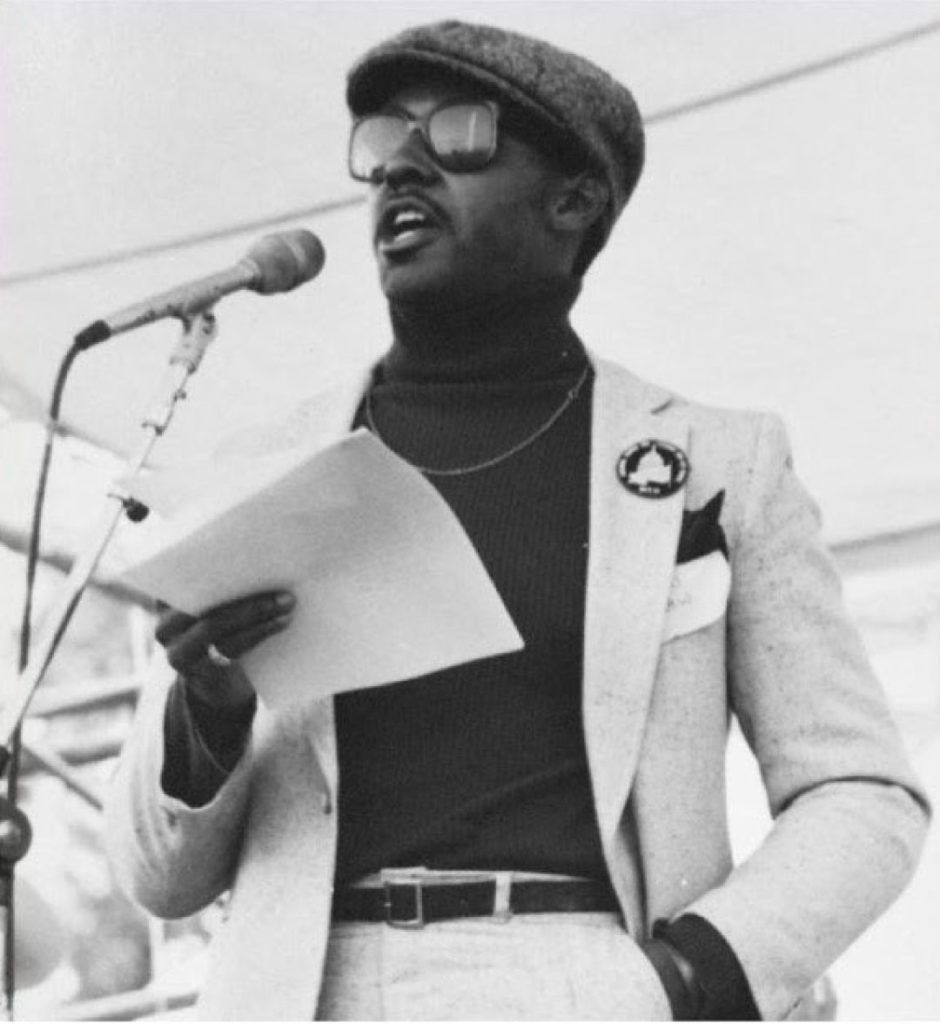

Bessie Smith. Photo by Regan Vercruysse.

Bessie Smith, also known as “The Empress of Blues,” was one of the most popular and influential blues singers of the 1920s and 1930s. Her voice could be described very much like her personality—strong but sweet, growly when she needed to be, and dulcet in her delivery. Described by those who knew her as a bold and confident woman who was as warm and loving as she was rowdy (she once chased several KKK members from one of her tent performances), Smith never shied away from singing her truth—and never shied away from living it, either. Her lyrics often indicated the way she felt and reflected the way that she lived; she was a sexual being and proud of it—characterized by many as unladylike, but Smith never cared. She was known to have various lovers when on the road, both men and women, and, though hardly the first Black bisexual jazz singer, Smith was unique for an entirely different set of reasons. Her voice and music inspired future vocalists like Aretha Franklin and Billie Holiday; and her talent not only earned her a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, but also got her inducted into both the Blues and Rock and Roll Halls of Fame.

Before Bessie, not a lot of Black music made it into mainstream popularity. Of course, this was the time period in which minstrel albums were being produced and were fairly popular, but people wanted to hear Black voices—real Black voices. And boy, did Smith deliver. In 1923, her first solo recording—Down Hearted Blues—sold an estimated 800,000 copies, kickstarting the upward trend of her music’s popularity. Following that, the whopping 160 recordings that she made between 1923 and 1933 even further solidified her success.

The magnitude of Smith’s achievement and wealth was not seen as something that would have typically been possible for a Black woman in the segregated South. But that was the thing about Smith—she was naturally defiant. Smith defied the expectations imposed upon women, especially Black women, of her time period by simply being herself—the loud, proud, unapologetic, openly bisexual woman that she was. Her attitude may be best summarized by the first line of her song “T’aint Nobody’s Bizness If I Do”:

“There ain’t nothing I can do, or nothing I can say

That folks don’t criticize me

But I’m goin’ to do just as I want to anyway”

Barbara Jordan

February 21, 1936–January 17, 1996

Houston, TX

Barbara Jordan

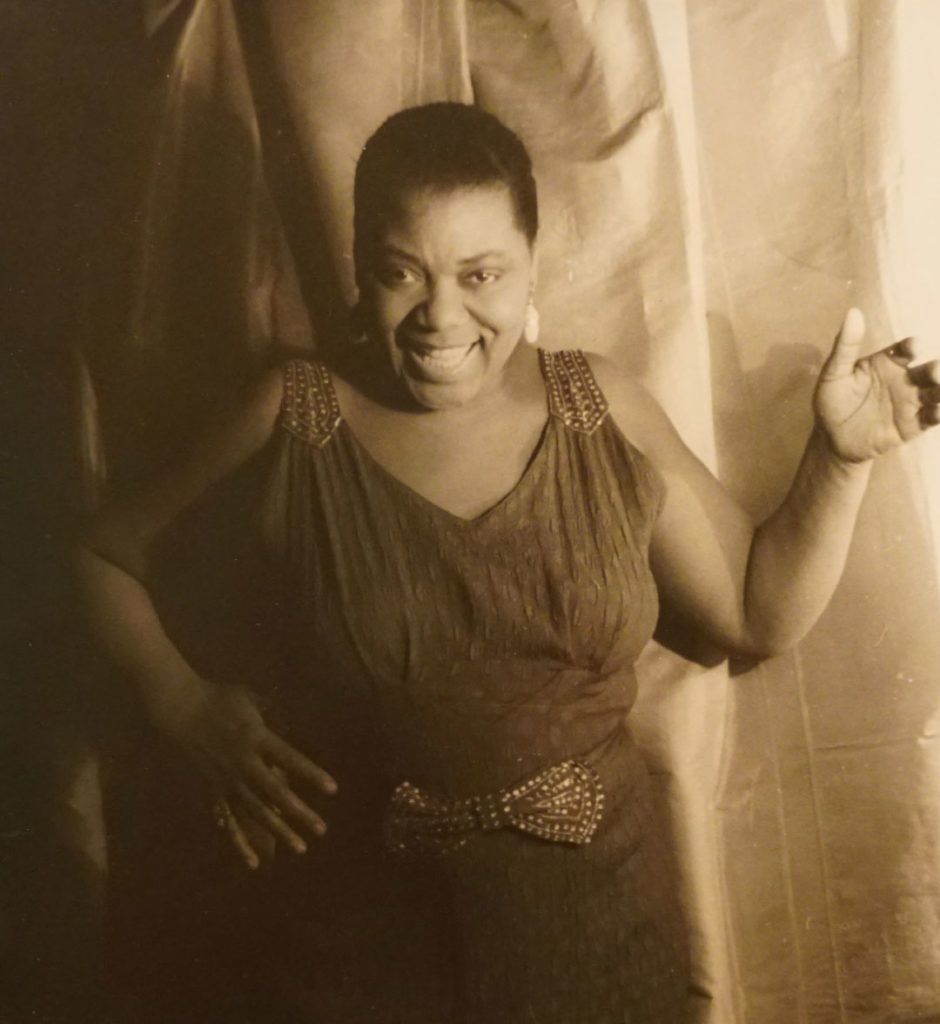

There are few Americans who are unfamiliar with the name Barbara Jordan, and even fewer Texans. During the prime of her political career, she was a household name. Jordan was not only a renowned educator, attorney, and politician, she was the first Black woman to be elected to the Texas Senate; the first Black keynote speaker at the Democratic National Convention; and the first Black Texan to be elected to the U.S. Congress. Those are a lot of firsts—and that’s not all of them. She broke color and gender barriers within the world of politics and beyond. She knew the significance of her triumph, recognized it, and aligned it with purpose, stating during her 1976 keynote speech at the DNC: “My presence here is one additional bit of evidence that the American dream need not forever be deferred.”

Over time, Jordan was recognized as a monumental figure of eloquence, integrity, and sound judgement. When she would approach a podium to speak, the crowd would immediately erupt into applause before quickly dying into silence in anticipation of hearing her speak. Regardless of the topic, people wanted to hear her every word—not only because her strong voice and precise pronunciation was enjoyable to listen to, but because there was always something profound in her message. She spoke purposefully and did not waste words, which helped her to gain a following that extended beyond the boundaries of political parties, and to make allies of those who did not always subscribe to her platform. She was a strong and proud woman, but also a private one. Publicly, she was very clearly, very deliberately the Barbara Jordan that she allowed the world to see.

From 1973 until her untimely death in 1996, she suffered from a variety of illnesses including multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and leukemia—all of which she endured quietly and tried to hide from the public. This was not the only personal issue that she kept from the public eye. It was not until the Houston Chronicle published the name of her “longtime companion,” Nancy Earl, among Jordan’s list of survivors in her obituary that the public learned of the nature of their relationship—something only extremely close friends and associates had previously known. Jordan was a woman who had loved a woman; it is a concept that many today still struggle to accept, and avoid affirming (though there is pretty concrete confirmation—including things like images at home, the references to Earl at Jordan’s funeral, and a note addressed to the two of them in the University of North Texas archives). The news of Jordan’s sexuality struck LGBTQ Americans in different ways and triggered various responses—the most famous being an article by The Advocate that many of Jordan’s personal friends begged the publication not write. The piece, which published just two months after her death, was entitled, “Barbara Jordan: The Other Life,” and criticized Jordan for keeping her lesbianism a secret. The following issue of The Advocate contained numerous letters written by members of the public who disapproved of the Barbara Jordan piece, each condemning the magazine for chastising the late Jordan for the preservation of her private life.

Barbara Jordan was an amazing woman who changed history for Black people, for women, and for all Americans throughout her life. She worked tirelessly to be everything America needed her to be. My only wish is that she could have seen all of the out and openly–queer political figures and candidates today; to have seen that all America really needed her to be was openly and authentically herself.

Lucy Hicks Anderson

1886–1954

Waddy, Kentucky

Lucy Hicks Anderson (c)

The life of Lucy Hicks Anderson, formerly Lucy Lawson, is known to be one of the earliest recorded stories of a Black transgender person in America. Though the term “transgender” did not yet exist in her lifetime, she was personally aware that a person could be born biologically as one sex, yet identify and live as another. From a very young age, she was adamant that she was, in fact, a girl, and insisted on wearing dresses and that her name was Lucy. Her mother, unsure of what to do, took her to a physician who prescribed that she raise and rear her as a girl—so that’s what she did. Lawson started working domestic jobs at the age of 15 and, when she entered her twenties, moved west to live in Pecos, Texas, where she resided for a decade before meeting her first husband, Clarence Hicks. Together they moved to Oxnard, California, where she continued her career of domestic work, working her way up from cooking and childcare to assisting in preparation for and hosting elaborate dinner parties for the wealthy families of the area. Over time, she saved up enough money to open and operate a bordello and speakeasy during the prohibition period, a business venture that proved incredibly successful. She soon became quite the socialite herself; hosting her own sumptuous celebrations and dinner parties and giving generously to charity whenever she could. She truly became an integral, distinguished part of the community. During WWII, not only did she purchase almost $50,000 dollars in war bonds, she would throw parties for enlisted soldiers before they went off to war. And if word came back that a local boy died in action, she would drive to the family’s home to offer emotional support while they mourned. Though racial inequality still prominently existed during this time period, wealthy white women would drive to Hicks’ home to ask for her recipes; and notable officials would request her assistance in making sure their event went off without a hitch.

In 1929, Anderson and her first husband divorced, and in 1944, she remarried to a soldier named Reuben Anderson. They lived and worked happily together in the town for about a year before a series of events changed everything. First, the U.S. Navy traced a venereal disease back to Anderson’s bordello and conducted an investigation. The local doctor, Hilary R. Morgan, insisted that every woman go through a thorough exam—and though Anderson did not participate in sex work, that she be examined too. The examination ultimately revealed that Anderson was not assigned female at birth. This was news that quickly spread and, though the community had willingly looked the other way for over a decade as Anderson ran her speakeasy and brothel, the moment they discovered she was transgender, they offered no support, turning their backs on the once-revered community member. As a result, Anderson was tried by the Ventura County district attorney for perjury. Because she was claiming her husband’s GI benefits at the time, she was charged with defrauding the U.S. government and falsifying marriage documents (by swearing that there were “no legal objections toward marriage”). She was then required to undergo a series of additional examinations by various doctors to verify the sex she was assigned at birth. Despite the harassment she endured and the pain of betrayal she felt, Anderson stood her ground. She told the jury that a person could appear to be of one sex, but actually be of another. When she took the stand, she rightly testified that she’d lived her entire life as a woman. She firmly asserted that the sex that she had lived as for her entire life was more valid than what was printed on her birth certificate: “I defy any doctor in the world to prove that I am not a woman. I have lived, dressed, and acted just what I am—a woman.” It was in this moment that Lucy Hicks Anderson became the first trans woman to defend her marriage in court; it also marked the first ruling against a trans individual’s marriage in court—an injustice that too often persists today.

Following the trial, Anderson and Reuben’s marriage certificate was declared null and void. She and her husband were both sentenced to jail, and Anderson received an additional 10 years of probation upon her release. While imprisoned, the court prohibited her from wearing any feminine clothing. She was 59 at the time. After serving their sentences, the couple attempted to return home to Oxnard, but were warned by the town’s Chief of Police that Anderson would be arrested if they were to settle there again. Excommunicated from the town they called home, the couple moved to Los Angeles and quietly lived out the rest of their lives in the city. In her final years, I’m sure Anderson could only dream of today, a time when she is celebrated for the woman she was, and will always be.

Willmer “Little Ax” Broadnax

December 28, 1916–June 1, 1992

Houston, TX

Willmer “Little Ax” Broadnax. Photo courtesy The Trans Guys.

The story of Willmer “Little Ax” Broadnax is phenomenal for a number of reasons. First, Broadnax’s life is one of the earliest recorded accounts of a Black transgender man in America (though he was not identified as a trans man until after his death). Second, Broadnax was not an unknown figure—he was a showman known by many across the nation.

Broadnax, nicknamed “Little Ax” because of his small stature but powerful voice, was born and raised in Houston, Texas. He got his musical start early on alongside his brother, William “Big Ax” Broadnax, with the St. Paul Gospel Singers. From there, he moved cities to join another singing group, The Southern Gospel Singers in Los Angeles. This group performed primarily on weekends, as most of its singers had day jobs. This schedule made it difficult for Broadnax and the group to get touring gigs, an issue which ultimately led him to create his own quartet, The Golden Echoes—a group in which both he and his brother sang. The group became vastly popular, eventually becoming one of the top touring gospel quartet groups of the 1940s.

Some time later, Broadnax’s brother left The Golden Echoes to join The Five Trumpets in Atlanta, Georgia, while “Little Ax” stayed to lead the Golden Echoes. Despite their revered reputation and growing success, the group disbanded in 1949. Broadnax moved on to sing with the Spirit of Memphis Quartet, one of the great gospel groups of the 1950s, until 1952, before switching to perform with the Fairfield Four in Nashville. Then, in the 1960s, Broadnax worked with the chart-topping Five Blind Boys of Mississippi as a replacement for Archie Brownlee. During this decade, Broadnax also lead a revived version of the group he founded his career with, the slightly renamed “Little Ax and the Golden Echoes.” After the popularity of gospel quartet music declined, Broadnax retired from performing for the most part, occasionally still subbing for members of the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi in the 1970s and 1980s.

Simply put, Broadnax was a talent. His strong and distinctive tenor voice enriched every track he sang on—and when he took the lead in a song, not only did you hear the power in his voice, but you heard his passion. A performer for over three decades, he dedicated his life to the music he loved; once he started, he never stopped.

In 1992, Willmer Broadnax was murdered by his girlfriend, who stabbed him during an argument. Only after the autopsy was it discovered that Broadnax was originally assigned female at birth. The news initially shocked the gospel community, but was predominantly swept under the rug; in fact, while researching for this article, the majority of sources I found did not even mention his trans identity. This omission erases the fact that, for several decades, the gospel community loved and respected a talented transgender man. The bravery that Broadnax had to live as his authentic self in a time and within a community that was far from trans-friendly makes his story all the more admirable.

—

There is power in knowing that there were people before you—that were like you—that made a difference in the world. While we do not need permission to be ourselves, the ability to trace our identities back through history gives us perspective—a comparative parallel that allows us to not only see where we come from, but how far we can go, given that we embody similar ideals and improve upon them. We don’t want to merely survive as Black queer individuals anymore—we want to live freely, without lifelong censorship. Our history is much more than just a series of stories, anecdotes, and old pictures; our history is a model for our future and the foundation for our appreciation of the present.

It’s disappointing how many Black queer people come out to their families only to be told, “Black people don’t do that.” If only they’d known the names and stories of Charles Law, Bessie Smith, Barbara Jordan, Lucy Hicks Anderson, and Willmer Broadnax—Black people who did just that, and did it well.