By Josh Inocéncio

Just minutes before we departed the house for a night flight to Vietnam, my mom crept up behind me in our dimly lit living room and doused my neck with a few flecks of oil.

“Wooooh!” I gasped. “The hell was that?”

“It’s thieves oil,” she said plainly. “It has an interesting history. During the bubonic plague, pickpockets carried it so they could steal from corpses without getting sick.”

“I don’t care what it is,” I muttered, wiping my neck. “Ask me before you throw wet things near my face!”

Consent on this matter went nowhere. Hours later on the flight from Houston to Taiwan, she stirred my sleep by patting a cool face wipe on my forehead. After hearing my tales from Mexico City, she was bent on preventing malaria, dengue fever, or traveler’s diarrhea in Southeast Asia. She came prepared, even holding her nose as she bought DEET-filled bug spray.

No street food for this Kentucky gal. Not on her first jaunt outside North America. She’d quarantine me, if necessary.

But dengue fever would be the least of our mishaps.

The trip to Vietnam and Cambodia originated from a desire to see my friend Rae—an expat from Ohio and my spiritual twin sister—since she had moved to Saigon. Four years ago, we met through a mutual friend while Rae was living in South Korea—a country I was heading to for a five-week odyssey. We skipped pleasantries and connected immediately, recognizing our astrological polarity as a Cancerian and Capricorn (they’re each other’s opposing sign). There are some people you just know you’ve met in another life, and Rae is one of those for me. She helped me come out and, in the process, taught me a lot about sex and self-worth.

Now, my mother, Lenora, came with me, too. Our last mother and son venture—to New York City in 2014—was shattered of all joy when I came out to her as gay at the airport before we departed Houston. But hey, she coaxed me. That, and since my dad and I had hiked Mt. Fuji in Japan, my mom hungered for a trip with me. And I wanted her to go, especially amid the busyness of her new position at work. She longs to see the world, and we needed a healing adventure.

While she imagined her first getaway beyond the Americas would be to vineyards in Italy or rock cliffs in Ireland, she embraced the ruggedness of Southeast Asia. The moment you land and pick up an Uber from Saigon’s international airport, you know you’re in the jungle. From French mansions cloaked in banyan trees to humidity that makes Houston look arid.

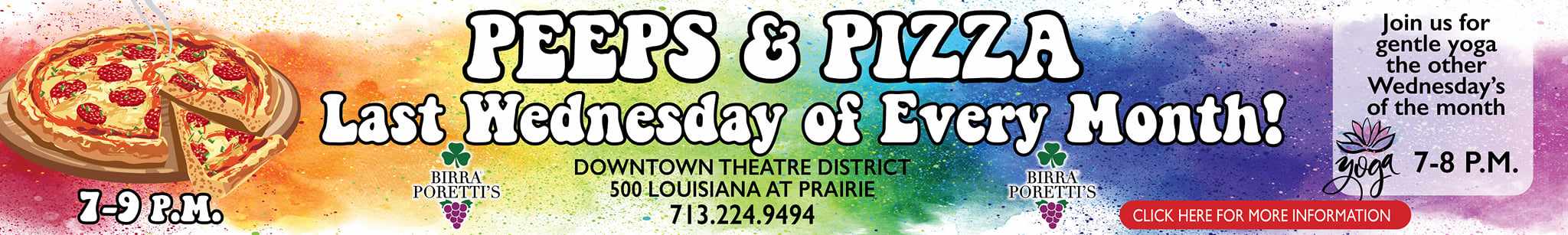

“You just trust in the universe,” admonished Rae over breakfast at the Snap Café when my mom and I asked how best to cross the humming motorbikes on Saigon’s streets.

There is a kind of invisible conductor that orchestrates motorbike drivers in Vietnam’s largest city, with little need for streetlights or traffic cops. Well-practiced pedestrians step confidently into this metropolitan symphony, as five or more lanes of drivers whir around them—a score my mom and I were hardly trained to follow after traversing 12 time zones the previous day.

But by the fifth day in Saigon, we were nearly as regular as the locals—not only briskly braving the streets, but also referring to Vietnam’s largest city as “Saigon” (residents refuse the communist-led switch to Ho Chi Minh City).

Josh Inocéncio (l) chats with Rae at Snap Café in Saigon.

We sampled the French-inflected cuisine at L’Usine and Secret Garden, along with the craft beer culture bubbling in the city’s rooftops in places like Pasteur Brewery—all in District 1. We tackled the Ben Thanh Market where shopkeepers hustle you with items you can find at any booth within a two-foot radius.

And we faced the U.S.’s harsh history in Vietnam at the War Remnants Museum that, as its name suggests, doesn’t celebrate a Vietnamese victory, but rather displays the human cost of war with landmine injuries and Agent Orange effects still disfiguring people generations later.

We finished Saigon with a day trip to the Cu Chi Tunnels, an hour or so speedboat ride up the river, where Viet Cong guerrilla fighters had dug vast underground networks to outwit their southern enemies. We then met Rae for a final meal at Quan Ut Ut, the Anthony Bourdain-approved barbecue joint. As a southern boy, I can vouch—the ribs there are just as good as anything I’ve eaten in Memphis, Louisville, or Lockhart.

By the first weekend abroad, we were eager to escape the city for a beach weekend on a western Vietnamese island famous for its night market filled with shops and tanks of fish and lobsters you can choose for dinner. What we weren’t prepared for were the bats on Phu Quoc.

After a day of yoga, massages, and walking along the shore near our hotel, we settled in for the evening to read with the patio doors open (against my mom’s suggestion), letting a rainstorm breathe in. As we savored perhaps the most relaxing day in months, I glanced up from my collection of short stories to a bat gliding through the four-poster bed, inches from my face.

I hollered. I threw the book and the comforter. I darted into the bathroom, as my mom screeched with no idea as to why I was screaming.

“Bat! Bat! There’s a bat in the room!”

“Are you sure?! How do you know it wasn’t a bird?”

“It had serrated wings!”

We summoned a bellboy and together searched at least 20 minutes for the bat. But its destination remained unknown, and we were shaken for the rest of the night—shrouded in a mosquito net and dozing like birds with one eye open to catch the bat’s flutter.

At best, we wobbled to our next stop—Siem Reap to see Angkor Wat—after a sleep-deprived night. In between layovers, I had to talk us both down from rabies shots (bats can bite, after all, without inflicting severe pain). As soon as we unpacked our luggage in the new hotel room in Cambodia, we heard a chirping near the vent. The dread was clear on our flushed faces as we looked at each other: Not again. Not another bat.

Little did we know, geckos chirp like birds and bats. We unveiled the tiny reptile, behind a curtain, squeaking away.

In this booming city in one of Asia’s poorest countries, the jungle is even closer than in Vietnam. While travelers stay here to see Angkor Wat—the largest religious building in the world—Siem Reap is worth a visit on its own. The day before the temples, my mom and I shopped at the markets, then had the most well-paced day of eating since we arrived. On Pub Street, we tried the Khmer (the name of the largest ethnic group in Cambodia) fish amok at the Red Piano—famous as Angelina Jolie’s “favorite bar”—and Khmer barbecue at Easy Speaking that included frog, beef, chicken, and alligator. Then we walked over the Bug Café, a French-owned restaurant with delicacies like doughnut with tarantula, spring rolls with ants, or bee cream soup. We played it safe and stuck to cheesecake with a layer of crickets—crunchy legs, but no stingers or venom.

But Siem Reap is popular because of Angkor Wat. We rose early after ordering a tuk-tuk and rode to the temple for sunrise. The bank in front of the temple brims with tourists from all over the world awaiting the first splashes of blue then pink as the yawning sun creeps from behind Angkor Wat. Before you hike into the temple, the bats are picking their last minute snacks and the birds are rising for breakfast. But after you make rounds through the temple, you can catch macaques picking fruit for their babies and slapping dogs.

Ankor Wat isn’t the only site to see, though. The entire Angkor complex includes Angkor Thom, once a royal residence; Ta Phrom, advertised by locals as the section with the “Tomb Raider Tree”; and, among others, Sra Sang, the lion-flanked royal baths. The complex requires at least a day and travelers should rent either a tuk-tuk or bicycle to travel between sites.

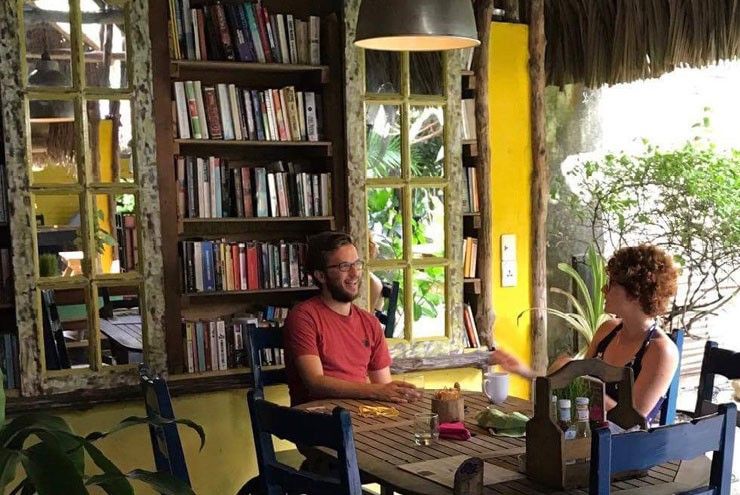

On the final day in Siem Reap, we took a cooking class with a group named Champey that takes you to the market to buy ingredients and then to a cottage where you cook a three-course meal with other classmates. Afterward, my mom and I grabbed beers at a nearby pub and, in one of the more significant moments in the years since I’d come out, we checked out guys. Particularly a Dutch-looking fellow a few tables away.

Josh Inocéncio (r) with his mom in their Champey cooking class.

“How come I never see you with blondes?” she mused.

“Mom. It’s not like I report every hook-up to you,” I said, sipping my pale ale and glancing again at Mr. Netherlands. “There have been scruffy blondes, okay?”

We drank in silence for a beat, and I grinned.

But if I can recommend one event beyond the temples, it’s the completely human Phare Circus.

Behind the majesty of Angkor Wat, Cambodia suffered through one of the most horrific genocides of the 20th century. The Khmer Rouge, led by the dictator Pol Pot, took over Cambodia in the 1970s—as Vietnam descended into further conflict—and exterminated 25 percent of the population. Survivors of that conflict and their descendants still wrestle with PTSD—and the performers in the Phare Circus, all of them children who once lived on the streets, craft acrobatic pieces with stories that confront their nation’s troubled history.

The last major leg of our trip was in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital and the former stronghold of the North. A stark contrast from Saigon, Hanoi beams with communist pride—shops in the Old Quarter sell re-prints of propaganda and the infamous Hanoi Hilton (the prison museum where Sen. John McCain was once held as a POW) celebrates Vietnamese political prisoners who resisted French colonial rule. Saigon, meanwhile, prides itself on its history of rebellion in the South—an irony not lost on this Texas boy and his Kentucky mother, as our own regional homeland fleshed out a war over “southern pride.”

Despite a trek into the political epicenter of the city where you can visit President Ho Chi Minh’s mausoleum and house, we clung mostly to the Old Quarter and French Quarter. The Women’s Museum is worth a visit—particularly the exhibit on women guerrilla fighters during the Vietnam War. We ate multiple times at Pizza for Ps (which has the tastiest pizza I’ve ever eaten in the world), chilled at the mostly expat-populated Hanoi Social Club, and caught a traditional water puppet show at Than Long near Hoan Kiem Lake.

My mother, adjusting to the spigots attached to toilets in Asia, created her own water puppet show, too. During a break at a lounge where we grabbed drinks to cool off from the humidity, she emerged from the restroom with dripping hair and a soaked shirt.

“What happened?” I asked.

In between giggles, she managed to describe her battle with the hose that’s used to rinse your butt. As she tried to freshen up, she lost control of the hose, wrangling it like a feisty serpent, as it sprayed her stall, her face, and her clothes. Already drenched from the heat, she worked in an accidental shower.

We’d had fun on this trip. But we hadn’t laughed like that in ages.

In a way, we faced our individual and mutual fears on this trip. We both fought off the bat dread—and we repaired what was once a troubled mother-son trip. “I don’t want any arguing between you two,” my dad would say before we left. As a kid, my mom and I had a penchant for fighting “like brother and sister”—a relationship we were confused for constantly in Vietnam. But the most remarkable part of the journey was how little conflict edged in and how easy it was to enjoy each other.

My anxieties of reliving New York four years ago were waylaid and buried.