By Nikita Shepard

Forty years ago, Félix González-Torres arrived in New York City from Puerto Rico, marking the beginning of his emergence as one of the most influential conceptual artists of his generation. During a brilliant career cut tragically short by his death from AIDS, the openly gay, Cuban-born, Latino-American artist produced a wide range of works that challenged spectators to participate in the creative experience and to formulate their own meanings. Through photography, billboards, and installations comprised of everyday objects, he evoked themes of loss, desire, longing, travel, the passage of time, the vulnerability of the body, the merging of public and private, and the connection between art and politics.

I first encountered the art of Félix González-Torres back in 2010. I had embarked on a much-anticipated trip to Washington, DC to see the National Portrait Gallery’s controversial gay and lesbian exhibit Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture. Tucked into a corner among the photographic prints and paintings, I noticed a deceptively simple sculpture: a pile of candies individually wrapped in colored cellophane and piled into a pyramid. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) consisted of 175 pounds of candy, corresponding to the weight of his lover, Ross Laycock, before his deterioration and eventual death from AIDS.

‘Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)’ by Félix González-Torres. Photo: henskechristine

During the brief interval I spent considering the sculpture, I saw three people pluck candies from the pile and move on to other pieces in the gallery. (174…173…172…) Something about the installation and the interactions I witnessed with it vividly evoked a sense of haunting absence, the vulnerability of the steadily vanishing body, the casual indifference of the passersby to the wasting and disappearance masked behind the colorful façade. Before I left, I tucked a red-wrapped candy into my pocket, fingering it over the coming days as I reflected on the exhibition and the magnitude of our community’s loss from the epidemic.

Félix González-Torres was born on November 26, 1957 in Guáimaro, a small town in the southeastern corner of Cuba’s Camagüey Province. His birth took place barely a year before the revolution that would turn the island’s traditional subordination to US political and business interests upside down. After spending his early childhood in provincial Cuba, he and his sister were separated from their parents and moved temporarily to a Catholic Church-run orphanage in Madrid, before relocating to Puerto Rico to stay with an aunt and uncle for his teenage years. He began his formal art studies in 1976 at the Universidad de Puerto Rico in San Juan, where he became an active participant in the local art scene.

In 1979, he relocated to New York City, attending the Pratt Institute and participating in the Whitney Independent Study Program. His studies whetted his fascination with critical theory and postmodernism, while his engagement with the city’s vibrant queer subcultures and underground art scenes inspired his creativity.

After earning his MFA from the International Center of Photography in 1987, he joined Group Material. This New York City-based artists’ collective promoted political activism and community education, while producing critical works addressing themes such as consumerism, US foreign policy, and the AIDS epidemic. Over the course of his short but prolific career, González-Torres would participate in hundreds of group art shows and was the subject of several prominent solo museum exhibitions. Unlike some of his intentionally obscure predecessors among postmodern conceptual artists, he believed in the importance of engaging the public. He spoke enthusiastically about his artistic practice and philosophy while encouraging viewers to take part in co-creating the experience of the work. As he maintained, “I need public interaction. Without the public, these works are nothing. I need the public to complete the work. I ask the public to help me out, to take responsibility, to become part of my work, to join in.”

Navigating the white-dominated artistic and academic worlds of New York, he stood out as a Latino and an immigrant. As he recalled in a 1992 interview:

“When I went to art school at New York University there weren’t any Hispanics around except for the elevator man. When I started to teach at N.Y.U. in 1987 I used to joke that the elevator man’s name got onto the teacher’s list by accident. On the list of fifty-five teachers, I had the only Hispanic-sounding name.”

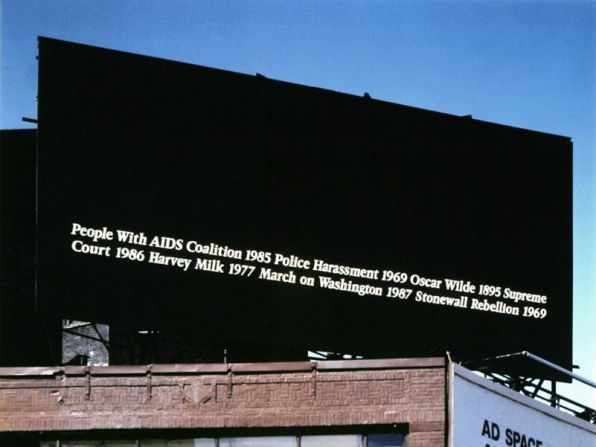

In addition to his racial and cultural difference, he lived as an unapologetically gay man, and while he resisted descriptions of his artistic practice that reduced him to his identities, affirmations of homoerotic desire and queer culture appeared in some of his early prominent public works. In commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion in 1989, he produced a billboard that appeared in New York City’s Sheridan Square. With a stark black rectangle augmented only by a white caption juxtaposing events, figures, and years significant within queer history, he appropriated a space associated with consumerism for artistic and political expression.

In commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion in 1989, Félix González-Torres produced a billboard that appeared in New York City’s Sheridan Square.

He intended such gestures as reflections on the disintegration of the distinction between public and private, a point driven home painfully for lesbians and gay men by the 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick decision, in which the Supreme Court ruled that states could legally enforce bans on same-sex sexuality, even within one’s own home. As Gonzalez-Torres commented, “Someone’s agenda has been enacted to define ‘public’ and ‘private.’ We’re really talking about private property, because there is no private space anymore. Our intimate desires, fantasies, dreams are ruled and intercepted by the public sphere.”

Another famous untitled 1991 billboard consisted of a black and white photograph of a double bed, whose rumpled sheets and indented pillows indicate the ghostly presence of absent figures. Like the candy pyramid, the work was intended as a memorial for his partner Ross Laycock, who had recently died of AIDS. The image injects the private and intimate into the glaringly public format of the billboard, evoking through its absent traces “the love that dare not speak its name” while memorializing what critic Tom Folland describes as “a tangible if disappearing presence.”

This untitled billboard by Félix González-Torres was intended as a memorial for his partner Ross Laycock, who had recently died of AIDS. Photo: Paul Keller

The subtlety and open-ended ambiguity of many of his photographs and installations reflected both a critique of the cultural authority of the artist as well as his distinct philosophy of the political value of art. As he explained:

“Aesthetics are not about politics; they are politics themselves. And this is how the ‘political’ can be best utilized since it appears so ‘natural.’ The most successful of all political moves are ones that don’t appear to be ‘political.’”

Other works illuminated the consequences of gun violence, the vulnerability of democracy, or themes of citizenship, migration, and travel, evoked through stark squares of red, strings of lightbulbs that slowly burned out, or stacks of blank “passport” booklets.

In the last years of his life, he split his time between Miami, Florida, and New York City, until he became too ill to travel. The disease whose toll he evoked so hauntingly in his artwork would eventually take his life—he died from complications of AIDS at the age of 38 in Miami on January 9, 1996. His death came just one month after the FDA approved the use of saquinavir, a protease inhibitor that, in combination with other drugs, formed the “highly active antiretroviral therapy” (HAART) medication regimen that would begin to save thousands of lives of HIV-positive people in the coming months.

Like many other Caribbean-American Latinx migrants, González-Torres lived a life that challenged the regional logic of “the South” through its diasporic flows and transnational connections. For these communities, Cuba and Puerto Rico form a circuit with Florida and New York City in which people, cultures, and ideas flow across oceans and borders. As Julio Capó Jr. reminds us in Welcome to Fairyland, his path-breaking history of queer Miami before 1940, the circulation of queer desires and bodies through these Caribbean and southern networks stretches back well over a century.

Tracing Latinx lives that span Caribbean islands and American cities opens a window to a reconfigured vision of the South, where race goes beyond the Black/white binary of the Confederacy and Jim Crow, and US aspirations to imperial domination of Cuba and Puerto Rico matter as much as the Lost Cause. And paying attention to queer migrant lives reveals how the tracks laid by military conquest, tourism, and migration allowed new conceptions of gender and desire to flow through the region as well, reconfiguring the sexual culture of the South.

This October 15, communities around the country will observe National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day.

Félix González-Torres belonged to many places: to the Cuban and Puerto Rican cultures that raised him, to the New York art world where he made his mark, and to queer Latinx Miami where he was laid to rest. And today, his artistic legacy lives on—not only in prestigious institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, but in the hearts of the thousands of artists and ordinary queer folks like me who have been moved and inspired by his creative vision.

To date, over 125,000 Latinx people have died from HIV/AIDS in the United States, and continue to be disproportionately affected by the disease. This October 15, communities around the country will observe National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day, with events taking place all over the country. In memory of Félix González-Torres and so many other bold and brilliant queer and Latinx people we have lost to the disease, check out the Latino Commission on AIDS to find out ways you can show support or plug in. States with scheduled events include Virginia, Florida, Texas, South Carolina, and other places across the South.

References

Capó, Jr., Julio. Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami Before 1940. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Cruz, Amada, Suzanne Ghez, Ann Goldstein, and Nancy Spector, eds. Félix González-Torres: America. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2007.

Folland, Tom. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres, ‘Untitled’ (billboard of an empty bed).” In Identity, The Body, and the Subversion of Modernism (online course, Khan Academy). https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/global-culture/identity-body/identity-body-united-states/a/felix-gonzalez-torres-untitled-billboard-of-an-empty-bed

Rollins, Tim. Félix González-Torres. New York: Art Publishers, 1993.

Spector, Nancy. Félix González-Torres. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1995.