Editor’s note: This is part one in a three-part series on teaching Houston’s queer history.

By Trevor Boffone

When I began teaching Intro to LGBT Studies at the University of Houston in Fall 2016, I barely took the local queer community into consideration when I designed the course. Aside from having my students watch the documentary A Murder in Montrose about the Paul Broussard murder in 1991, my course was largely void of queer Houston content. This was surprising given my focus on local communities in my research and advocacy work. Even so, while discussing the events following Paul Broussard’s murder with my students in Spring 2017, I recognized that this group of queer and ally Houston residents had little to no knowledge or understanding of queer Houston. Sure, a handful of them were familiar with Houston’s gayborhood, Montrose, but even then, mostly spoke to the neighborhood’s nightlife. No student in the room was aware of Montrose’s history or of the long struggle for equality that queer Houstonians have faced.

In my mind, because of this, I was doing a disservice to my students—especially ones on the LGBTQ spectrum—who should understand the longstanding queer history of the city they call home. Queer students should know more than big names like Harvey Milk or events such as the Stonewall Riots. While that history is foundational, Houstonians should be aware of the evolution of Montrose into a fully-fledged gayborhood, the 1977 night Anita Bryant came to town, and the ongoing battle for legal protections following the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance’s defeat in 2015.

With this in mind, I set out to learn as much as I could about queer Houston. When the Fall 2017 semester rolled around, I was ready to overhaul my course to make a more inclusive effort to teach Houston. This is my obligation as an educator. I know my students can be changemakers; they just need the tools to do so.

Below I detail a handful of major moments in Houston’s LGBTQ history. These are the moments that I used as a starting place to build my course. By no means are these events comprehensive. To learn more about Houston’s rich queer past, visit the Houston We Have History Banner Project.

Montrose Becomes the Gayborhood

Brian Riedel, assistant director of the Center for the Study of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Rice University, is a true expert of queer Houston. His work involves tracking the locations of gay bars in Houston (See: “Mapping Montrose’s Gay History” by Leah Binkovitz). His charts show how gay bars began to congregate in Montrose in the mid-1970s. According to Riedel, this growth continued into the 1980s, leading to the “heyday” of Montrose’s queer culture in the 1990s. As John Nova Lomax writes for Texas Monthly, “When Austin was still a relatively straitlaced southern college town, Montrose had already unfurled its freak flag.” In “My Montrose,” William Broyles claims that Montrose is the birthplace of Texas counterculture, not Austin. While the neighborhood still features a high concentration of gay bars—especially in the square bracketed by Fairview, Westheimer, Montrose, and Taft streets—the number is lower in recent years. This decrease has led some to claim that the area is in fact no longer a gay neighborhood, something that also reflects Houston’s inclusive nature—LGBTQ residents feel safe living and building community in many parts of the city. Even so, LGBTQ folks, especially transgender people, still face higher threats of violence and marginalization.

Anita Bryant Comes to Town

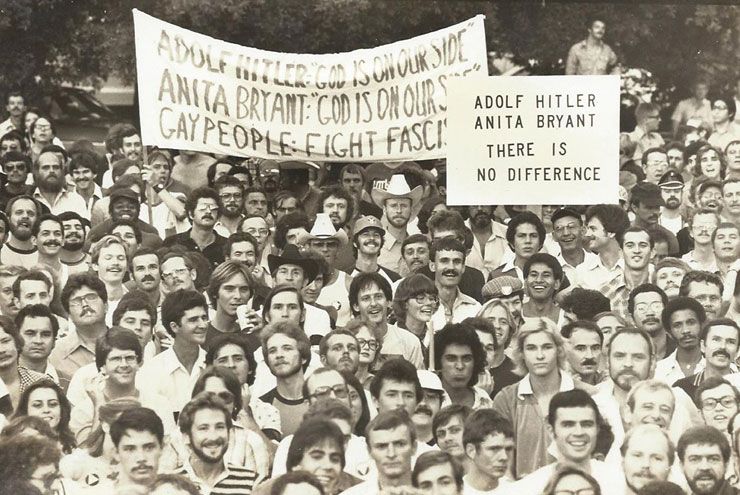

Houston held its first Pride march in 1976—six years after NYC held the very first Pride. The relatively small march only included about 120 people. It wasn’t until a year later in 1977—when famed anti-gay activist Anita Bryant came to Houston to perform at the Texas State Bar Associations’ annual convention—that Pride in Houston took off. Bryant’s presence in the city angered and rallied the LGBTQ community, leading to thousands of people participating in a Pride march that organized the emerging queer community. (For more on the event, see: Andrew Edmonson)

Tragedy Strikes

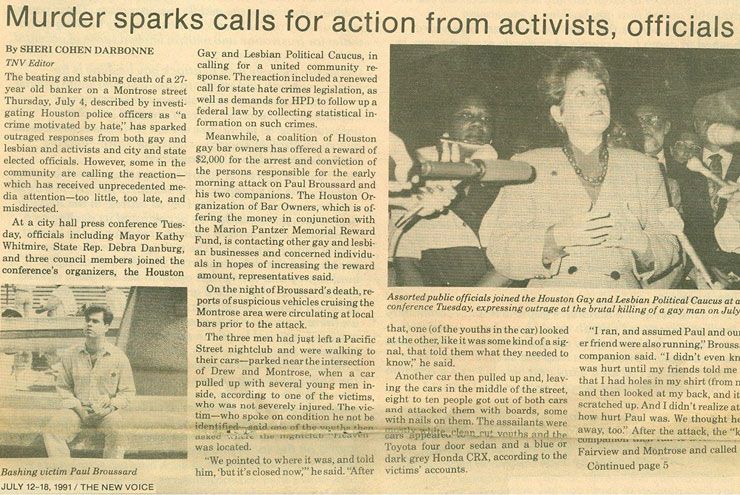

As depicted in the Houston Public Media documentary, A Murder in Montrose, the local LGBTQ community was rocked by the brutal murder of 27-year-old banker Paul Broussard. The Texas A&M University alum was walking to his car after going to a gay bar in Montrose when the so-called “Woodlands 10” attacked him. After beating him up, Jon Buice stabbed Broussard, ending his life. This defining moment galvanized the community. By 1991, Montrose had seen an increase in anti-LGBTQ violence and queer Houstonians demanded the city protect its LGBTQ citizens.

The 1991 murder of gay banker Paul Broussard sparked queer Houstonians to demand the city of Houston protect its LGBTQ citizens. Photo: Houston Public Media

In response, the queer community held a march for action at the intersection of Montrose and Westheimer that culminated with everyone sitting down in the middle of the street. This was their neighborhood, and they weren’t going to move until the city of Houston responded. Ultimately, the murder helped motivate the Texas Legislature to pass hate crime legislation and transformed Harris County’s criminal justice system. In many ways, the murder set off a wave of activism that continues into the present day.

Moving Forward

Admittedly, Houston’s queer history is far too expansive to adequately give it justice here or in a semester-long panoramic Intro to LGBT Studies course. Thankfully, others have taken on this work; Brian Riedel, Andrew Edmonson, Leah Binkovitz, and Emily Deruy regularly write about this history, exposing the myth that Houston is nothing more than an oil and gas city. There is so much more to Houston than meets the eye; more than what’s taught in schools and universities; and so much that is left out of the public imagination. We see the effects of this erasure when equality measures such as HERO don’t pass. To put it simply, people need more queer education.

In the following two parts of this series, I detail specific teaching strategies I’ve used to engage my students with queer Houston. One thing is certain: making Houston the focal point of the semester has thus far been transformational—not only for my students, but for me as well.