By Anna Burns

While history often seems bereft of queer lives, nothing could be further from the truth. Transgender people have always been around in one form or another, though the terminology that we’ve used to describe ourselves has changed over time. Much of our history has either been purposefully destroyed, as in the case of Nazis burning queer books, or is reinterpreted through a modern cishet lens. Because of this, it is important to reclaim queer figures in history, such as the transgender empress of Rome Elagabalus.

However, before we can discuss this noteworthy but controversial empress, we must first determine a working definition of “transgender,” as it relates to historical figures. This definition is complicated by how terminology has changed over time. Further, one can never be totally sure of the mental state of a historical figure since our access to them is through writing, often translated, and through the lens of time and culture. To that end, and for the purposes here, one of two criteria must be displayed to establish a historical figure as trans: one, a stated preference to be a gender other than the one the individual was assigned at birth; or two, living as another gender for a long period of time with no other known goal.

For example, someone assigned female at birth (AFAB), who presents as male solely for the purposes of joining a military would not count. Someone like Dr. James Barry (1789–1865 CE), however, would be considered transgender because, although he was AFAB and did join the military, he continued to live as male for the remainder of his life.

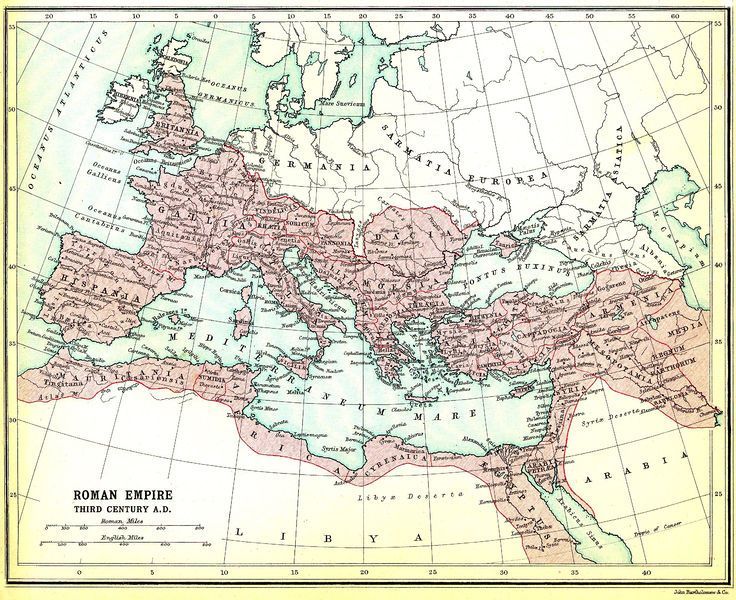

I argue that the woman depicted in the bust above, Empresses Elagabalus, would also be defined as a transgender historical figure. She was born in Emesa (present-day Syria) circa 204 CE, and was assigned male at birth—given the name Varius Avitus Bassianus. Elagabalus was born into the Severan Dynasty through her mother’s side, making her a niece to the Emperor Caracalla. Elagabalus’ father served as a senator to the emperor. In 217 CE, a high-ranking civil servant murdered the emperor in an attempt to usurp the imperial throne. Elagabalus’ mother spread rumors that Elagabalus was the child of the late Caracalla in an attempt to restore the dynasty, putting her daughter forward as the true, legitimate heir to the empire. In The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, author Edward Gibbon records that Elagabus’ promise of restoring the Severan Dynasty was enough to get the military on her side. After engaging the forces of Marcrinus at Antioch on June 7, 218 CE—where Elababalus herself was involved in a cavalry charge, and proved herself victorious in battle—she declared herself empress.

She arrived in the city of Rome in the fall of 219 CE. She took the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, with the byname of Elagabalus, after the Syrian god Elagabal. Elagabalus attempted to force the empire to follow and worship Elagabal, a move which would prove widely unpopular. It also played a notable part in her downfall only three years later. Elagabalus also created a women’s senate (at the Quirinal Hill). And though it did not last long, the woman’s senate was seen as morally corrupt and disgraceful, a mockery of true government (as the thought of the day was that women could never lead). This and other machinations, like murdering an heir, ultimately led to her execution at the hands of the Pretorian Guard.

A map of Roman rule shortly before the start of Elagabalus’ reign. Map created by Bartholomew, John & Co; Smith, George Adam 1925

At first glance, Elagabalus appears to be a fairly standard, mid-to-late Roman ruler: ineffective and prone to excess. Understanding the major events of her life is important, but even more important is to analyze her possible existence as a trans woman.

In Elagabalus’ case, I would put forward that there is good evidence she met both aforementioned criteria of being transgender—she preferred to live as a gender other than the one she was assigned at birth, and lived this way as a choice of its own end. Yet, even here, there are historiographical issues, as the primary sources available are very biased, and Elagabalus was not a popular empress—both due to her religious views as well as her attempted execution of her heir. Additionally, as Eric Varner would discuss in their book Transcending Gender: Assimilation, Identity, and Roman Imperial Portraits, attacking an individual’s sexuality and gender was common in Roman life. For example, there were rumors that Julius Caesar engaged in gay sex and was a submissive. Because of political attacks like that, some of the facts documented by authors such as Cassius Dio and Herodian need careful examination.

Turning to the available texts—first, does Elagabalus ever state a preference for being identified as female? To answer that question, one can turn to Cassius Dio’s Roman History:

Aurelius addressed him [sic] with the usual salutation, “My Lord Emperor, Hail!” He bent his neck so as to assume a ravishing feminine pose, and turning his eyes upon him with a melting gaze, answered without any hesitation: “Call me not Lord, for I am a Lady.”

Not only that, but Elagabalus is noted for wandering the streets of the capital looking for physicians, offering a large bounty to anyone who could alter her genitals. There is some confusion in the text here, however, as to whether Elagabalus wished the physician to alter her penis to appear more vulva-like, or to add a vulva. Yet, given the rest of the actions and words ascribed to her, I believe her to be a binary trans woman. Additionally, when she took a husband, she enacted the ceremony not as two men, but embodying a female role. The exact number of spouses she had is unknown, but she took at least five wives and one husband. Furthermore, in Herodian’s History of the Roman Empire since the Death of Marcus Aurelius, he records that Elagabalus retained the services of many male and female concubines. She also wore feminine attire from her home province. Beyond that, she also plucked her facial hair, wore makeup, and would, on occasion, wear a wig when she would go out to taverns.

So, the question now is, with the historiographical concerns of Roman historians, why would one believe these sources? After all, Roman historians had a fundamentally different view of what history is; they viewed history as records of the state, not personal lives, and as propaganda.

One of the most detailed primary sources of Elagabalus’ life, Cassius Dio’s Roman History, describes how Elagabalus ordered the round-up of children of noble birth and sacrificed them en masse. As Celia Schultz writes in “The Romans and Ritual Murder,” human sacrifice during this time was relatively rare. Although the early Romans had several rites that would end in a person’s death (for example, killing visibly intersex children), after the mid-to-late Republic era, they viewed human sacrafice as distasteful. It was, in fact, one of their justifications for going to war with the Celts.

Clearly, Elagabalus was an unpopular empress, so might her transgender nature be an invention of these chroniclers, rather than something grounded in facts? While not a total impossibility, there exist three primary sources that record her life and, importantly, affirm her transgender identity.

One of these, Marius Maximus’ biographies, is lost to time, but was used as the primary source for Aelius Spartianus, Julius Capitolinus, and Vulcacius Gallicanus’ Historia Augusta, published one to two hundred years after Elagabalus’ death. These histories disagree on many things, such as human sacrifice. Dio is the only author who claimed she practiced the act, while the other two (Herodian’s History of the Roman Empire since the Death of Marcus Aurelius and Historia Augusta) both talk about how Elagabalus sacrificed animals in a non-Roman fashion. Yet, all three of them agree that she preferred to be referred to as a woman. As such, modern histories should take her trans identity and pronouns into consideration.

Statue of a Gallus Priestess, 2nd century; located in the Capitoline Museums in Rome. Photo by Anna-Katharina Rieger.

Moving from Elagabalus to the wider empire, how would the average person at this time view a trans person? And what types of social roles did trans people fill? Most often, references to transgender people (as they would be defined today) appeared in religious contexts, most notably in relation to the goddess Cybele, whose cult was officially adopted during the Roman Republic’s Second Punic War. The individuals seeking to join her clergy would be castrated alongside a possible ritual rebirthing. In her text In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele, author Lynn Roller points out that there is no record of people who were assigned female at birth joining Cyble’s cult in the Imperial era. During its procession day, the cult’s followers would leave their temple quarters and parade in celebration. They were reported to wear feminine clothes with long, bleached hair, heavy makeup, and jewelry. They would tell fortunes (even the Roman senate would, on occasion, call upon them to tell military fortunes), play music, and, on mourning days, flog themselves. Though a long-standing cornerstone of Roman religious life, lasting long into the Christian era, the cult’s clergy was seen as distasteful and Roman citizens were barred from joining.

The nature of writing histories during the Roman Empire means that little evidence exists on how people interacted with and viewed their transgender neighbors. Unfortunately, the two most prominent examples were in positions of religious and political importance, which creates complexities when attempting to sort out society’s view of transgender existence. Even with that disclaimer, it appears that, overall, Roman culture did not hold transgender lives in high regard. Different cultures in the ancient world handled transgender people with more or less understanding and compassion, but sadly, it appears that the Romans believed that transgender people as a whole were scandalous and a threat to polite society.

While the past is the past, we are the ones who write our histories. The Romans may not have respected Empress Elagabalus’ gender, but it is on us to correct those mistakes and recognize the queer lives that came before our own—regardless of how turbulent they may have been. We belong to an ongoing legacy that has endured millennia. Though there are attacks on our rights in the current political climate, we can take solace in the fact that neither we, nor our history, can be erased.

References

Augustine, S. (1998). The City of God Againist the Pagans (Vol. 7). (R. W. Dyson, Trans.)

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dio, C. (1927). Historia Romana (Roman History) (Vol. LXXX). (E. Cary, Trans.) New York:

Harvard University Press.

Gibbon, E. (2003). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Abridged Edition. New York:

The Modern Library.

Herodian. (1961). History of the Roman Empire since the Death of Marcus Aurelius. (E. C.

Echols, Trans.) Berkeley: University of California.

Kubba, A. K., & Young, M. (2001). The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry MD.

Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, (pp. 352-356). Edinburgh.

Lancellotti, M. G. (2002). Attis Between Myth and History: King, Priest and God. Leiden : Brill.

Lisdorf, A. (2019). Traumatic Rites in the Cult of Cybele and Attis: A New Perspective.

Roller, L. E. (1999). In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Schultz, C. E. (2010). The Romans and Ritual Murder. Journal of the American Academy of

Religion, 78(2), 516-541.

Spartianus, A., Capitolinus, I., & Gallicanus, V. (1924). Historia Augusta (Vol. 2). (S. H. Ballou,

& D. Magie, Trans.) New You: Harvard Univeristy Press.

Varner, E. R. (2008). Transcending Gender: Assimilation, Identity, and Roman Imperial

Portraits. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes(7), 185-

205.

Wasson, D. L. (2013, October 21). Elagabalus. Retrieved from Ancient History Encyclopedia:

https://www.ancient.eu/Elagabalus/

Anna Burns

Anna Burns is a graduate student in psychology at Alabama A&M University. Her clinical interest lies in sex & gender. She also likes otters, reading, talking about psychology, and has more knowledge of Star Trek than may, strictly speaking, be wise.