By Yvan Oliva

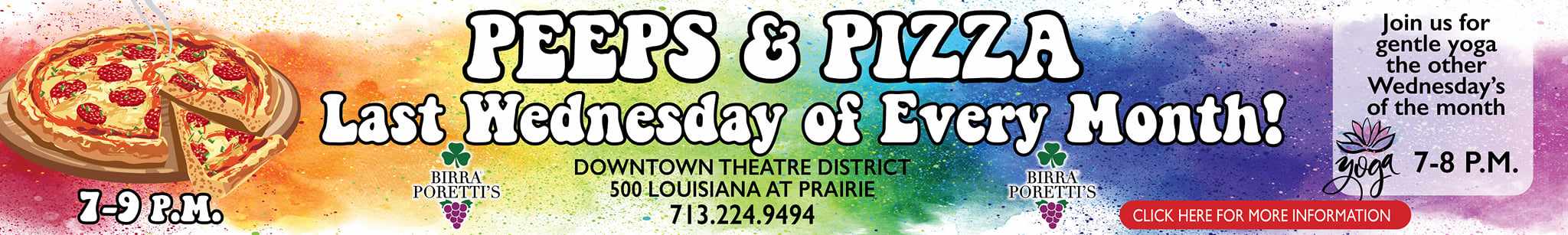

At some point in time, somewhere in Guadalajara, Mexico, this picture was taken. My Abuelita Guadalupe, my mother’s mother, sits between her sons David and Moises. In 1973, she would take my mother, Patricia, and her son Carlos with her across the border here to Houston. Some of her other children were already in Texas, while some never crossed. Abuelita would be diagnosed with Leukemia just four years later and, as such, decided that she wanted to die in her own country. My mother was 18, had already moved out of the house, and would remain close to her sisters here, Chelita, Julie, and Irma. In 1983, Tía Julie would take this photo to be developed and gift it to my mother for Christmas. That’s Tía Julie’s signature on the back, her tall figure waving a flag. (She would sign most personal notes this way. Cute, no?) Many years later, after my mom had borne all four of her children, I would be riffling through a plastic tote full of photographs and stumble across this image.

I’ve always had this uneasy feeling, due to my lame capacity for recollection, that my memories might actually be tied to specific images that I’ve been exposed to, like home movies of birthday parties, family outings, and other small moments that occurred against the backdrop of our domestic family life. So much of the living moment seems to have escaped my notice that these photos help me create a recognizable path, albeit one rooted in the entropy of memory. These images became springboards of inquiry for me from a young age, ever since I became cognizant of the fact that my mother had a mother as well, even though I never got the chance to meet my Abuelita Guadalupe. Elsewhere in these photos was evidence of a connection to this woman and to the country where her spirit rests.

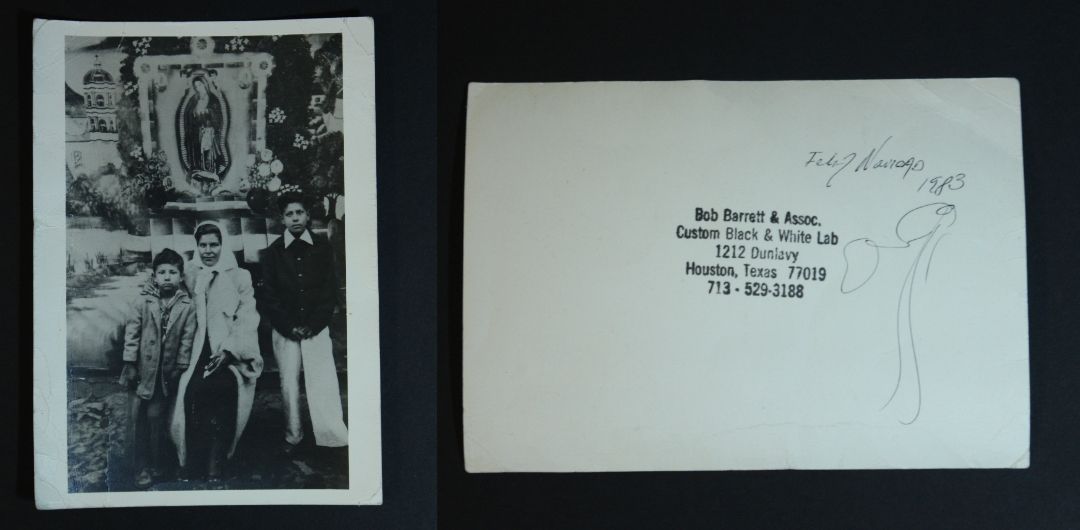

My siblings and I grew up, at least in the early years, speaking predominantly Spanish in our childhood home in Alief, Texas. To help us acclimate to the English language, which was spoken all around us and in our schools, we would be given translation prompts, words and sentences written in Spanish, and we were tasked with producing the English version of them. It worked both ways though, as sometimes the words were translated into Spanish.

Mi casa es grande y amarilla.

My house is big and yellow.Mi gato duerme en el patio.

My cat sleeps in the patio.I remember sitting at our tiled dining table under yellow fluorescent light producing these translations, unconscious of the fact that what I was doing was traversing two modes of experiencing the world. One exemplified the English-speaking world through which we navigated as hyphenated Americans, while the other was a connection to a world we were told was at the core of our being, something that “we could not forget.” Later on, the process of translation would help me to recognize the gray area of my existence, the liminal space in which I choose to define myself and move through the world, a borderlands of the interior. When I finally recognized myself as trans, translation became a means through which I could render the text of my body into a language closer to my imagining, a union of those two tongues housed within.

Mi cuerpo es un mundo.

My body is a world.

Just last week, I was huddling next to a space heater at work because it was 50°F and my workplace is a warehouse made of thin metal walls. This week, it’s been nothing but rain, overcast skies, and highs in the 70s. Apparently by Sunday, we’ll have dropped back into the low 40s. No Houstonian should be surprised by the volatility of our weather though, as it’s one of those “charms” about the city that we’ve just come to accept. Besides, I can relate to this aspect of our subtropical metropolis: volatility.

Once a week, I take an injection of estradiol, 20mg of it right by my belly button. It’s lipid-soluble, so my externally supplied hormones are slowly absorbed over the course of the week. But it’s those 24 hours that both precede and succeed my injections that can be the most volatile. On my comedown, I can feel so numb, absolutely bereft of any real attachment to my surroundings. Other times, I can settle into a comfortable melancholy and shed a good couple of tears after devouring a pint of vegan ice cream. My come ups exhaust me more—temperamental, vexing irritability, punctuated with a sadness that seems to seep from the marrow of my bones. Volatile. But it’s in this act of feeling worse that I in turn feel closer to myself, forced to reconcile with the visceral realities that occur when our thoughts and emotions dump ceaseless buckets of rain on our psyche. A feeling, to me, is a harbinger from the body that it requires something, that it is hungry because, to quote our goddess of words, Ocean Vuong, to “hunger is to give the body what it knows it cannot keep.”

Eat up, buttercup.