Editor’s note: This is the second installment in Spectrum South’s Historians of the Queer South series. Each month, we share a new article highlighting a scholar who we think has made a particularly important contribution to our understanding of the queer southern past.

By Nikita Shepard

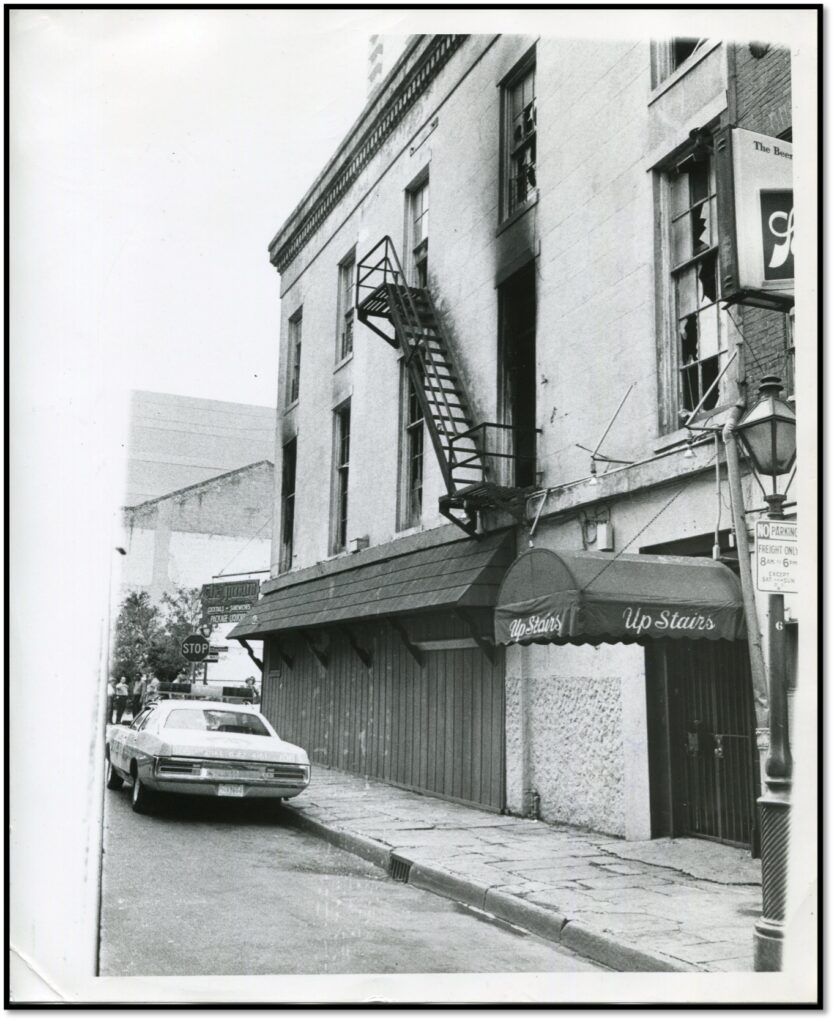

Fifty years ago this week, a horrifying tragedy struck the New Orleans queer community. On June 24, 1973, an arsonist attacked the Up Stairs Lounge, a French Quarter gay bar, killing 32 people. Until the Pulse massacre in Orlando in 2016, it was the most lethal attack on the LGBTQ community ever perpetrated in the United States. Yet even today, few people have heard of it.

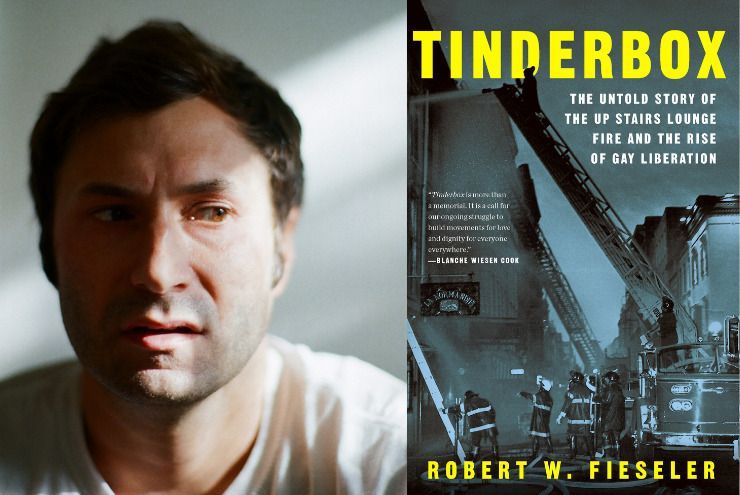

Robert Fieseler has done more to change that than nearly anyone. His 2018 book Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation won a slew of awards and quickly became the definitive account of the tragedy. I listened to the audiobook version and vividly remember the day I emerged from the subway with tears streaming down my face because I was so shaken by the book’s gripping narration of the fatal fire.

Given how powerfully the book moved me, and the importance of the events it recounts to queer southern history, I was delighted to make contact with the author during a recent trip to New Orleans. We sat down together at a cafe in the Bywater neighborhood near the home that he shares with his husband of 17 years. He greeted me with a square jaw, lively eyes, and a T-shirt printed with the logo of the LGBT+ Archives Project of Louisiana, a local queer history organization on whose board he sits. I immediately felt the kinship of a fellow queer history enthusiast, and he generously humored me as I piled on question after question; every time he apologized for “going on and on,” I assured him that I couldn’t be more delighted.

Over nearly three hours of avid conversation, I got the inside story behind the lethal fire and its impact on the history of LGBTQ New Orleans. And I also gained a glimpse into the power of queer stories to dramatically alter the course of a life, as well as the power of a determined community to reshape how we remember critical moments in our collective past.

Robert Fieseler never imagined he’d wind up living in the South. Raised in the suburbs of Chicago, he recalls, “The common Midwestern presumption is that the South is somewhere to fear, a dangerous place that tried to overthrow Lincoln (and then killed him), a region with a civil rights record out of a horror film.” He smiles wryly. “As a Midwestern kid, you learn the painful, necessary history lessons, but you don’t get an on-the-ground education in southern hospitality, live music, cuisine, the landscapes, or anything redeeming that might paint the South as somewhere people might actually want to live.” Still, his encounters with New Orleans in literature sparked his curiosity—Anne Rice novels, A Confederacy of Dunces, and especially Christopher Rice’s scorching gay thriller A Density of Souls, which he read aloud to his college boyfriend. “It was as if the words were dripping off the pages, it was so hot!”

But it took a career change and a chance encounter to find his way to the city. After building a successful life in Chicago and London working in advertising and corporate copywriting, he left it behind to pursue his passion for journalism. After graduating from Columbia University’s School of Journalism, where he studied to become a subculture reporter, he was looking for his next big project when one fell into his lap unexpectedly. Over lunch in New York one afternoon, a journalism contact who knew of his interest in gay history and politics mentioned the 1973 Up Stairs Lounge fire. It piqued Fieseler’s interest; how had he not heard of such a horrifying and pivotal event in queer history? There must be a story to be told there.

So he packed a bag and headed down to New Orleans, initially staying with friends for three months “in a wisteria-scented sunroom in the Carrollton neighborhood.” His initial research netted enough information to come up with a proposal: “I thought it was great, but the editor shot it down.” But the city had gotten under his skin, and he was determined. Six months and a lot of redrafting later, he came up with the right pitch, got the green light, and would spend the next four years in and out of Louisiana researching his first book—which would become an LGBTQ publishing sensation and permanently alter the way we understand queer southern history.

The book’s opening chapters paint a vivid portrait of New Orleans’ gay community in the early 1970s, particularly the working-class gay men who patronized the Up Stairs and attended the city’s Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), a gay-and-lesbian-inclusive Christian congregation. The bar provided a welcoming refuge in a city that, despite its free-wheeling and hedonistic reputation, could still prove hostile to its queer inhabitants.

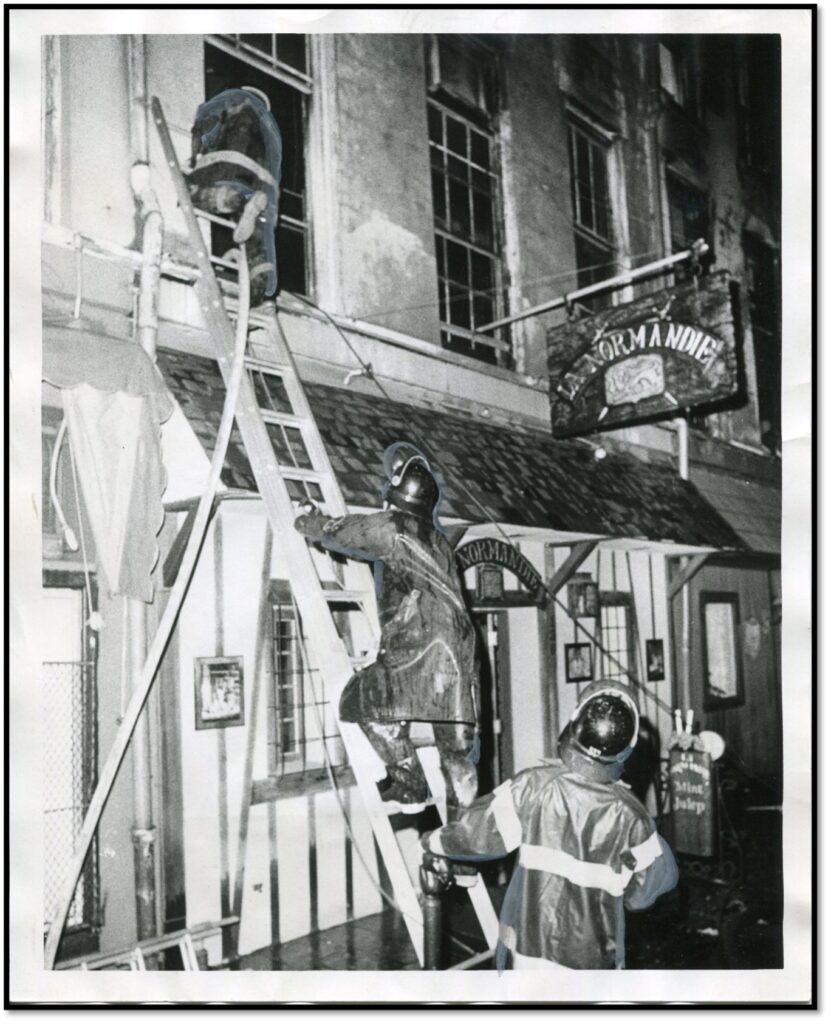

But that sense of sanctuary was permanently ruptured one warm June evening, as the weekly “beer bust” drink special was winding down and dozens of patrons relaxed by the piano. Someone squirted lighter fluid in the staircase leading up to the bar and ignited a blaze that rapidly spread upwards. In just 16 gruesome minutes, the blaze gutted the building. By the time the smoke cleared, 28 lay dead—four more would die from their injuries in the coming days—and more than a dozen others were injured. The charred bodies of two long-term partners were found locked in a final embrace.

As if this senseless loss of life was not horrible enough, homophobia shaped the city’s response to the tragedy. Local churches refused to host funerals for the victims, while some families left bodies of the deceased unclaimed out of shame. The mayor, away on a taxpayer-funded vacation to Europe, offered no comment. Media coverage either ignored or denigrated the sexuality of the victims, while police and fire department investigations were rife with anti-gay hostility. The city’s overall response was to sweep the awful event under the rug. It would take decades for a real reckoning with the Up Stairs Lounge fire to take place—a process that is still unfolding.

Part of the challenge Fieseler faced in telling this story was that many gay residents at the time didn’t want it to be told. Much of New Orleans gay life at the time, especially among its upper crust, involved a genteel code of discretion, what he calls a “queer southern social compact,” which was disrupted by the public assertiveness of gay liberation. “To fully out yourself meant destitution,” Fieseler points out. “You could lose your class status and not be able to do all the fun party stuff that was so central to the city’s queer life.”

In the aftermath of the fire, tensions arose when coastal gay activists arrived to organize events and speak to the media. Rev. Troy Perry, the charismatic, southern-born MCC preacher who traveled from Los Angeles to support the local gay community, was accused of being a “fairy carpetbagger” when he bucked local norms by calling a press conference and using his real name. When the provisional coalition catalyzed by out-of-town activists dissolved after their departure, “the closeted elite gays went after the activists,” Fieseler explains.

However, accusations that Perry’s efforts were just a “publicity stunt” weren’t borne out by the history that followed. Tinderbox documents how some local participants in the initial press conference and memorial following the fire went on to become lifelong queer activists, including organizing the massive rally against Anita Bryant in 1977 that many saw as the launching point for gay activism in the city. As terrible as the fire had been, some in the queer community rose from the ashes transformed, laying the groundwork for a new generation of LGBTQ leaders to emerge.

One of the biggest questions lurking over the story is the most obvious one: who did it? Tinderbox advances a convincing theory of who actually committed the arson, which remains technically unsolved to this day. The book assembles an array of evidence pointing to Roger Dale Nuñez, a troubled drifter and gay hustler who often solicited drinks at the Up Stairs, who had been ejected from the bar earlier that evening. Like many who’d examined the attack, Fieseler first assumed it had been motivated by anti-gay prejudice; indeed, at the time, arsons against gay churches and community centers were commonplace. The deeper his research proceeded, however, “the more I could see that the perpetrator was most likely from within the community, with a history of violence and deception intertwined with internalized queer hatred.” The psychology fascinated him: “I can relate to internalized queerphobia; I wanted to explore it.”

While we will probably never know for sure—Nuñez committed suicide the year after the fire—Fieseler says he’s “98 percent sure” that the fire was set by Nuñez, or else was a completely random incident. “It’s enjoyable to pretend to be Sherlock Holmes,” he admits. “I did hope some unsettled questions would be, if not resolved, then at least clarified. Several were, but others were not.” He’s a meticulous researcher, but he hopes that Tinderbox won’t be the last word on the story.

Fieseler readily acknowledges the other researchers on whose work he built: “I couldn’t have written Tinderbox without the prior books.” In particular, the historians Johnny Townsend, who conducted interviews with survivors of the fire for his 2011 book Let the Faggots Burn, and Clayton Delery, who dug deep into records of the police and fire department investigations for his 2014 study The Up Stairs Lounge Arson, generously shared their research and insights.

How do you tell a story so long buried, when so many didn’t want it to be told? While building on the efforts of previous scholars and conducting his own extensive archival research provided a foundation, Fieseler knew that to get at the deeper story—the personalities, the intrigue, the local color, the subtexts—he’d have to immerse himself in the community. Here, his mild-mannered Midwestern approach served him well. “I’m still kind of polite and deferential—though not nearly as much as I used to be!” he laughs. “People here like to talk, and if you keep quiet and listen, they’ll like you if you give them time to sound off. I just kept going with that.”

As he made friends and gained trust in the community, he began to hear stories that challenged his stereotypes about southern gay life. He relates a salacious anecdote about a well-respected political columnist for a local gay newspaper in the 1970s who was well known for his penchant for leather and “water sports” (kinky sex play involving urine): “He would get chained to the wall above a bathtub at a bar off Decatur Street, fed pitchers of beer, and offer to pee on anyone who passed by!” Fieseler grins wickedly. “That’s the thing: he was a gloriously sexually depraved person and a respected journalist as well—and these elements weren’t separate, they were integrated parts of him.” These sorts of stories weren’t just titillating; they gave the author insight into the city’s underground queer sexual culture, where defying southern norms of respectability didn’t mean forfeiting respect in the community. “I thought, I love this place!”

Ultimately, Tinderbox is a story about the city more so than any of the particular people who populate its pages. “I tried to make New Orleans the biggest character in the book,” he explains.

Fieseler and his husband, a public works artist, have taken to their New Orleans life like catfish in a bayou. “In the Midwest, you’re taught to be agreeable and fit in, as if the worst thing in the world is to stick out,” he chuckles. “This middle-class sense that the opinions of others are supremely important, so you become a chameleon, not your real self—that doesn’t work here.” People in the Crescent City, he’s come to realize, aren’t impressed by fame: “The only celebrity in New Orleans is New Orleans.”

At this point, he’s been here almost five years and can’t imagine leaving. “If this place gets into your pores, it takes a lot to move away.” He flashes a wry smile. “It’s just so weird, that if you’re weird, too, it’s a bummer to go back somewhere you have to explain yourself all the time.”

His enthusiasm for history that surfaced during the research for Tinderbox has led him into another career pivot. This fall, he’ll begin a PhD in history at Tulane University, where he’ll build on his already formidable skills as a journalist and writer. But he’s already completed his second project, another deep dive into the South’s queer history—this time in the state of Florida. The new book, due out next year, will excavate the legacy of the notorious Johns Committee, which investigated civil rights groups and gay and lesbian communities in the 1950s and 1960s, leading to purges and arrests across the state. (FYI: Stacy Braukman, who wrote an important early book on the Johns Committee, will be profiled in our Historians of the Queer South series this fall, so stay tuned!) As an avid queer history buff, I can’t wait to see what project Fieseler turns his research talents to next.

But his work to commemorate the queer past goes beyond research and writing. Since the publication of Tinderbox, Fieseler has undertaken a number of different public activities in New Orleans to ensure that the fire and its victims are never forgotten. As a journalist, he was taught that he was “not supposed to change anything”—but he’s not satisfied to merely report on the past. “There’s so much more that people can do,” he insists. “There’s an activist angle to advance public awareness, and that’s critical.”

And he’s been busy. At the city’s National World War II Museum, he organized a public lecture discussing the military veterans who died at the Up Stairs. He collaborated with members of the New Orleans City Council on the text of a resolution formally apologizing for the city’s failures in the aftermath of the fire. That effort led, in turn, to joining an LGBT liaison task force with the New Orleans Police Department, working to move them toward making a public apology and active restitution for the failures of the original investigation and acknowledging the legacy of anti-LGBTQ bias in law enforcement. Efforts to secure a meeting with the city’s Catholic archdiocese have proven more challenging. “Because the fire touched so many dimensions of New Orleans society,” Fieseler maintains, “it can become a means to address various factors in queer life in the present-day context.”

Astonishingly, there are still three victims of the fire who remain unidentified half a century later, buried in the city’s “potter’s field” (a mass cemetery where the poor are anonymously interred). Fieseler is active in efforts with archaeologists to pinpoint the burial location of Ferris LeBlanc, one of the fire’s victims buried there who was eventually identified, so as to exhume and rebury him respectfully, and hopefully to take forensic steps to determine names for the three still unidentified victims. Although ultimate justice is impossible, Fieseler acknowledges—“You can’t revive these wonderful people who perished due to no fault of their own in an act of terrible, terrible violence”—he continues to fight for the city to take steps “to undo some of the disrespect they faced in life and death, and to memorialize their stories with more sensitivity and dimension.”

2023 marks the 50th anniversary of the fire, and Fieseler has been at the heart of a variety of efforts to remember the tragedy and commemorate its victims. Through a committee of the LGBT+ Archives Project of Louisiana, he’s organizing a three-day conference from June 23–25 focusing on the fire and its legacy. Events include a panel discussion with historians who’ve researched the fire, screenings of documentary films, musical and dance performances, a commemorative religious service at a nearby church with a recitation of the names of the dead, and a “second line” (a unique New Orleans tradition of a public funeral procession through the city streets accompanied by a brass band). He hopes the conferences will “inspire the next wave of individuals who want to create art, do scholarship, write memoirs or poetry, or do other things to further this legacy.”

While most of us are celebrating Pride and all the progress we’ve achieved, let’s also take a moment to remember the tragedies that shaped where we are today. Thanks to Robert Fieseler’s research and advocacy, we have more tools than ever to ensure that we never lose sight of the heartbreaking and inspiring legacies of queer southern history.

Want to read Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation? Purchase a copy through ShopQueer.co, and the author will receive double the income they usually would. Spectrum South also receives a 10% referral commission when our readers shop through this link. Queer readers support queer writers!

Historians of the Queer South: Announcing a New Spectrum South Series

July 14, 2023 at 8:22 PM[…] Robert Fieseler Remembers the 1973 Up Stairs Lounge Fire (June 23, 2023) […]