Editor’s note: This is the third installment in Spectrum South’s Historians of the Queer South series. Each month, we share a new article highlighting a scholar who we think has made a particularly important contribution to our understanding of the queer southern past.

By Nikita Shepard

“Will someone please find out what the hell is going in Florida? We’ve had enough!”

Stacy Braukman and I share a laugh. The question she’s just posed feels all too pertinent. My longtime partner lives part of the year in Florida, and through him, I’ve been getting a front-row seat to the state’s noxious anti-LGBTQ, anti-Black, anti-immigrant, and anti-protest politics.

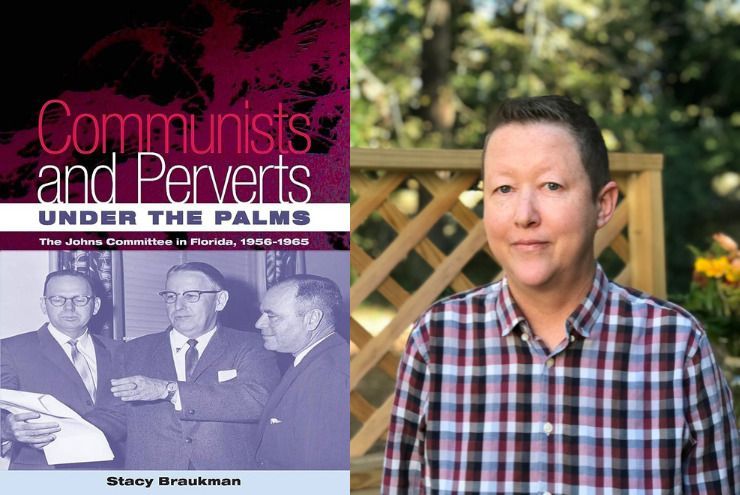

But Braukman has far more valuable insight into the history behind these politics than most of us. As the author of Communists and Perverts Under the Palms: The Johns Committee in Florida, 1956-1965, she spent years researching the roots of the state’s peculiar mix of homophobia, racism, and anti-radicalism as it arose in the years after World War II. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a state senator named Charley Johns founded and drove the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (FLIC), a homegrown version of the more widely known House Un-American Activities Committee central to the national Red Scare of the 1950s. FLIC, however—better known as the Johns Committee after its leader—distinguished itself by using anti-Communist rhetoric first as a bludgeon to fight the state’s Black civil rights organizations, and then in a wide-ranging purge of gay men and lesbians from state educational institutions. During its decade of operation, the Committee desperately attempted to hold onto power in the face of modernization and the cultural influence of an influx of new residents from outside the South. In the process, it ruined hundreds of queer lives and set back civil rights gains for years.

As a queer history buff, I found her book a remarkably lucid, intersectional, and powerfully moving study of a disturbing chapter in southern history, whose legacy lingers with us to this day. As we track the rise of Ron DeSantis and his transphobic and anti-Black efforts to combat “wokeness” in Florida schools and beyond—in part by controlling what we can teach and learn about the past—there are many lessons we can absorb from the history Braukman has done so much to document.

Stacy Braukman greets me with a soft-spoken demeanor and a warm smile that bubbles up often throughout the warm early summer afternoon we spent chatting on Zoom. She grew up in St. Pete Beach, Florida, across the bay from Tampa, where her mother was born and raised. Her grandparents were born at the turn of the 20th century and lived most of their 90-plus years in Florida. “They were southern to the core,” she assures me. “Some people think Florida’s ‘not the South.’ I can tell you that’s not true. It’s as southern as it gets.”

She dates her interest in questions of race and social justice to her experience in elementary school in the early 1970s, which she began during the early years of Pinellas County’s efforts to achieve school integration through busing. Braukman, who is white, didn’t realize at the time that these efforts to combine Black and white students and teachers in classes were seen by some in the county as a controversial experiment in “race-mixing.” Even as decades of civil rights struggles had begun to force long-overdue changes, the legacy of segregation cast a long shadow over the state she grew up in.

Braukman became fascinated with southern history during her high school and college years. At the same time, although she “was aware of feelings and possibilities,” she felt as if she had no access to information or mentorship around queer life. “We didn’t talk about it in school, in my family, in church,” she remembers. “I felt like I had no way of navigating what I was feeling.”

Though she didn’t have lesbian or gay mentors where she grew up in Florida, there were hints that she could only fully understand when she was older. “When we were growing up,” she recalled, “people would say things like, ‘Don’t go down to the gay beach!’ And I was like, ‘What are you talking about?’” Returning to the area as an adult, she realized that there was a section of the public beach where gay men congregated quietly to socialize and cruise, unofficial but an open secret. There was also a lesbian bar called the Lighted Tree on Eighth Avenue near the public beach. But as a teenager struggling to make sense of the landscape in the 1980s, she had nothing to go on but rumors.

She gradually began to come out while she was in college at Vanderbilt University in the late 1980s. Today, Nashville conjures an image of a fast-paced, progressive city with a large LGBTQ community amidst a conservative state. But at the time, it felt to her like “a small Bible Belt country town, extremely conservative, with no sense of queer community.” She took part in the campus’s first gay student group; “there were maybe eight of us” in the first meeting she attended, “and you had to put your first name, phone number, and college PO box in the campus snail mail to express your interest, then you would get a letter back with an invitation.” The power of the closet remained strong.

After college, she moved back to Florida, working at the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times) as a copy clerk while getting her master’s degree at the nearby University of South Florida. She attended her first (very small) Pride parade in Tampa in the early 1990s. “I was so nervous,” she remembers. “What if my picture ends up in the paper? Will my parents or grandparents see?”

It was around this time in 1993, during the summer after her first year at UNC-Chapel Hill pursuing a PhD in southern history, that the Florida legislature finally made the previously closed Johns Committee records public. She remembers how journalists swarmed the archives, writing story after story about how shocking it was that this committee existed, how scared people were, how damaging it had been. Some of these stories offered sensationalized coverage of the intrusive personal questions about sexual practices most people had been asked by the Committee’s investigators.

These stories were echoing in Braukman’s ears as she began to plan her own research as a budding historian at UNC-Chapel Hill. Knowing that she wanted to study race, social movements, and southern history, she’d originally been considering a project on the Daughters of the Confederacy in the mid-1990s. However, something about the Johns Committee stuck with her, and she was convinced that there was more to say about it than what was appearing in the news coverage. “I wanted to dig deeper,” she recalled, “and see what these people were thinking, or what they claimed to believe—and what shaped those beliefs.” As she entered into the mindset of the era, seeing how midcentury institutions of psychiatry, medicine, and law framed sexuality, she concluded that “it makes sense they would do that. It’s actually not surprising at all.” Homophobia, racism, and anti-leftism were all bound up together in the Committee’s work, and they would shape the political landscape in Florida for a generation.

Florida in the mid-1950s looked very different from the state today—and in other ways, all too similar. A small oligarchy of conservative Democrats dominated state politics and aligned with the interests of powerful agricultural and tourism magnates, drawing on white supremacy and religious zealotry to justify their control. In opposition, civil rights activists from the NAACP filed lawsuits on behalf of Black families in the state to enable their kids to attend integrated schools, while sit-ins and bus boycotts against segregation were taking place in Tallahassee, Miami, and elsewhere.

In this atmosphere of tension, longtime state senator Charley Johns took a vocal stance in defense of segregation and the white South. The Committee that would eventually bear his name began with a series of public hearings with NAACP leaders intended to demonstrate that the group was breaking the law, controlled by “outsiders” from up north, and full of Communists or at least Communist sympathizers. “People really believed this,” Braukman emphasizes. “If you were an NAACP member—especially the members who were white allies—they assumed that you must be a Communist and anti-American.”

But it wasn’t just civil rights activists and suspected leftists who came under scrutiny. Gay men and lesbians soon found themselves targets of the committee’s investigations. Exactly why the focus shifted from political and racial toward sexual unorthodoxy remains perplexing, but Braukman speculates that in the climate of the times, “it was just an easy thing to do, since gays and lesbians were so vulnerable.” She points out that the federal government and military had been purging suspected homosexuals for years, and that Cold War discourses framed “sex perverts” as threats to national security as well as to children. Also, Charley Johns’s son, who was a student at the University of Florida, reportedly told his old man that some of his professors seemed rather light in their loafers. Meanwhile, a state legislative committee investigating conditions in state-run tuberculosis hospitals in the mid-1950s found that one facility in Tampa employed a number of gay staffers, some of whom had ties to Hillsborough County schoolteachers and administrators. A list of names of sexually suspect public employees had already been compiled even before the Johns Committee arrived.

Although seemingly insignificant on their own, these scattered facts took on new relevance as Johns’s assault on the NAACP ran afoul of the courts, who demanded that the state halt their intrusive investigation of the civil rights organization. Determined to keep the investigations going, by 1957 the Committee was on the lookout for other scapegoats to target as untrustworthy or security risks. Gay men and lesbians, it seems, fit the bill. “When we consider what the average white person in Florida might have believed at the time,” Braukman explains, “that these were all legitimate threats to children and society . . . I think it made sense to them, I really do.”

Reading Communists and Perverts Under the Palms offers a chilling glimpse into the world of official homophobia during the 1950s and 1960s. As investigators fanned out across the state, determined to ferret out perverts in the ranks of teachers and students, they engaged in appalling violations of civil rights and basic decency. They used uniformed police to pull students out of classrooms and haul them off to interrogations without legal counsel in motel rooms; they solicited undercover informants and coerced people into naming names and snitching on members of their communities; they seized and read confidential medical records; and the list goes on and on. Many dozens of professors and teachers were fired; some attempted suicide, while others left town or fled the state.

Researching these stories proved an intense experience for Braukman. On the one hand, one of the real joys of researching the book came in the glimpses she got into the gay culture of the time: notes on how people dressed, specific places gays and lesbians congregated, and other details about queer lives in 1950s and 1960s Florida. On the other hand, she acknowledges, “The other part of me was heartbroken that people were subjected to this.” Despite her feelings of outrage, as a historian she found it more powerful to tell the story without editorializing, using excerpts from the documents to show rather than tell, forcing people to confront the truth of the past: “Here it is; this is what people believed. What are you going to do with it?”

The impact on Florida’s queer communities was devastating. As she continued her research, Braukman remembers reading letters written from folks in the state to queer friends and lovers elsewhere saying, “Don’t come to Florida, it’s too scary here, it’s too dangerous.” One longtime gay activist in Atlanta who had been at Florida State University in the late 1950s reached out to Braukman after the book was published. When he’d heard that his name was on the Committee’s list, he told her, “I left the state and never went back.” Some of the Committee’s targets may have stood up to their interrogators, but not much defiance appears in the surviving transcripts. More often, teachers would quietly resign and move away, students would withdraw from school or be expelled, and queer networks would go underground or dissolve entirely out of fear of exposure.

Ultimately, though, after years of spreading terror throughout queer Florida, the Committee dug its own grave at what it hoped would be its crowning moment. In 1964, hoping to justify its continued existence by shocking state audiences with its findings, the Johns Committee published a notorious pamphlet titled Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida. (You can read the full report here.) Its original cover featured two hunky shirtless men passionately kissing mouth to mouth, while inside it offered detailed descriptions of gay sexual practices and locales, photos of bondage and fellatio through glory holes, and more. And thousands of copies of this booklet were printed, at state expense, and mailed to community groups across Florida!

As you can probably imagine, this did not go over well. Hundreds of outraged citizens complained about this affront to their sensibilities, editorials across the state condemned the Committee’s prurient work (though most also condemned homosexuals, too), and after issuing one more report, the Committee folded the following year. Its reputation had been destroyed by the mockery and horror elicited by the report.

Braukman sheds light on why this appalling lapse in judgment made sense to the Committee at the time. “It was a common tactic among ‘decent literature’ activists at the time to shock people,” she explains. “The logic was, ‘We know this is bad, but you have to see it to understand the scope and nature of what’s happening out there.’” While on its own, Homosexuality and Citizenship seems like “a preposterous and wildly inappropriate document,” she notes that it was produced in partnership with the state’s extreme conservative segregationist governor, Farris Bryant, who had worked with the state’s Children’s Commission to educate Florida audiences about homosexuality and pornography. This granted the effort an air of legitimacy, a crusading self-righteousness that led the Committee to produce one of the weirdest anti-gay documents ever produced. In a bizarre denouement to the story, a gay publisher bought up leftover copies of the state’s report that it had shelved in response to the controversy, and re-sold them to titillated gay consumers! Not quite what the Committee had had in mind. . . .

Although the Johns Committee died an ignominious death not long after, it cast a long shadow. As Braukman’s own childhood in newly desegregating Florida indicates, it would take more years of struggle for some basic racial justice objectives to be achieved, while others remain elusive even today. As for LGBTQ Floridians, after a brief period of tentative emergence in the 1970s, the rise of Anita Bryant and her 1977 “Save Our Children” campaign in Miami-Dade County would make the state ground zero for a new wave of anti-gay politics. “Bryant had lived in Florida since the early 1960s,” Braukman points out. “She must have known about the Committee’s work.”

Today, Braukman sees what she calls “a ‘third wave’ of anti-LGBTQ hysteria” unfolding in the state, though she doesn’t know why it keeps happening in Florida in particular. And just like the time she describes in her book, “It’s no surprise that once again under the DeSantis regime, it’s not just about trans and LGBTQ issues—it’s about race, too. It’s about both.” Only an intersectional lens can help us make sense of how and why policies ranging from rewriting African American history curricula to banning inclusive discussions of gender and sexuality from classrooms fit together. It’s not a coincidence, she maintains, that “they want you to stop talking about it, they want you to stop teaching it.”

The right-wing furor today over these culture war issues reflects the ongoing legacy of segregation and homophobia that her book documents. This is why understanding the truth of southern history, including sensitive discussions of race, gender, and sexuality, is so important. “Whether white people admit it or not,” she explains, “there is something about the history of African Americans in this region that makes it inseparable from other white anxieties.”

Living through the political developments of the last decade in the U.S. has given Braukman new insights into its lessons. “When I was working on the book,” she recalls, “a lot of people looked at the Johns Committee and Anita Bryant as examples of backlash. At the time, I didn’t want to emphasize that, because it seemed more complicated to me.” However, having lived through the Trump years, she says, “Today I believe in that framework more. We’ve had a Black president, gay marriage, a shattering of fixed notions of gender . . . so much changed in what felt like a short time, and what did we get? Republicans like Trump and DeSantis.” She shakes her head and sighs. “You think you won? You didn’t win. We’re having to fight old battles all over again.”

Today, Braukman’s mother—who lived nearly her entire life in Florida—has moved away from the state permanently because of its bullying arch-conservative governor. “It’s a testament to just how bad things are there,” Braukman observes.

But despite how grim things seem, the historian in her sees grounds for optimism. “We’re not going back to binary definitions of gender, for example, and it’s difficult to imagine marriage equality being reversed,” she insists. “Some of these cultural shifts are permanent. And that’s a great thing.”

While she will always be a historian, today her energy focuses in other directions. In graduate school in Chapel Hill, Braukman had wonderful mentors, the freedom to study what she wanted, and a community of feminist historians who supported her work. She remembers those years fondly: “That was the best feeling in the world, to write that book, and to be around so many extraordinary people.” Ultimately, however, she decided that teaching wasn’t for her; she was interested in becoming an editor, and these days she works in communications as a senior writer and editor in Georgia. She hasn’t given up on history by any means; “I wish I could find another topic that spoke to me the way this did,” she laments, “but I haven’t found it yet.” In the meantime, however, she still avidly reads new work in history, writes reviews for journals, and stays connected to academia through friends and colleagues. As a result of her research on the Committee, Braukman was connected with Robert Fieseler, who we profiled in our Historians of the Queer South series earlier this summer, and whose forthcoming book will pick up where her research leaves off, digging deeper into the homophobic and racist legacy of the Committee.

Today, she lives in Atlanta, which she describes as “extremely gay and extremely wonderful.” That’s not to say there isn’t some risk, she acknowledges, “as there is for any queer person in any place ever.” But, she declares, “I think it’s the best place to be gay in the South, by far.”

Across the region, there’s a lot to be done. But learning from the troubling legacies of racism, homophobia, and anti-radicalism in Florida provides critical context for today’s struggles. And thanks to the work of Stacy Braukman, we can see clearly the ways that so many overlapping marginalized groups have been targeted and continue to be targeted by the same political forces—and the stake that we all have in joining forces to fight back.

Want to read Communists and Perverts Under the Palms: The Johns Committee in Florida, 1956-1965? Purchase a copy through ShopQueer.co, and the author will receive double the income they usually would. Spectrum South also receives a 10% referral commission when our readers shop through this link. Queer readers support queer writers!

Historians of the Queer South: Announcing a New Spectrum South Series

August 17, 2023 at 6:32 PM[…] Stacy Braukman on Remembering the Johns Committee (August 17, 2023) […]